Heritage Languages (9 Most Asked Q&A)

Until now, most public information about heritage languages has been in academic papers and journals.

These institutions and scholars have studied heritage languages and their speakers for decades, and have added an incredible contribution to human knowledge.

But many of the posts online don’t directly address the most common questions about heritage languages in a direct way.

And even fewer have given practical advice to adults looking to relearn their ancestral language or raise their kids to be bilingual in it.

Well good news: you’ve hit the jackpot.

In this article, we’re going to directly and succinctly answer the 9 most popular questions about heritage languages, their speakers, and how to relearn or improve your own heritage language.

Plus, in each section I’ll be linking additional resources, inserting videos, or giving you more ways to fall down the glorious rabbit hole that is the internet. They’ll all be academic resources, but they’ll all be open access so you won’t need a university account or to pay to view them.

In fact, this entire website and my work in languages is dedicated to sharing and popularizing heritage language research in the mainstream world.

So if you’re an HL speaker and want to learn more about your cultural heritage, feel free to take advantage of all of the free info on this site and on my YouTube channel.

If you want to see any other questions answered, you can leave them in the comments below.

This article is a living one--constantly being added to--so feel free to make any of your own contributions in the comments.

1. What is a heritage language?

One of the largest difference between heritage languages and dominant languages is the amount of schooling dominant languages receive

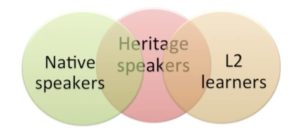

There are popularly 2 definitions of an HL: a broad definition and a narrow definition.

The broad definition is generally tied to the identity of a person and not their relationship to the language. It takes into account not just linguistics but anthropology and psychology as well.

The broad definition of a heritage language is a language spoken by one’s ancestors.

In this definition, it’s normally the individual in question who decides what their HL is.

The narrow definition is tied to the relationship between the language and the individual. It is a linguistic definition and tends to be favored by researchers or teachers.

The narrow definition states that a heritage language is a family language that an individual has some contact or experience in but is never fully developed.

In this definition, it’s often a school, teachers, administrators, or linguists who decide if a particular language is the HL of an individual.

But these two definitions seem contradictory, right?

Well, yeah. They can be.

And this is before we even attempt to get into other definitions of what heritage languages are!

Here’s a YouTube video I made that will give you a better understanding of why we have multiple definitions and why they’re all important. It’s a bit long, but I promise it’ll be more entertaining (and more educational) than any of the academic articles written on the subject.

Learn more about definitions for what a heritage language is:

- HL education in the United States

- Seeking explanatory adequacy: a dual approach to understanding the term “HL learner”

- Bilingualism, HL learners, and SLA research: opportunities lost or seized?

2. Can a heritage language different than a cultural heritage?

Absolutely.

Let’s give two examples of how an HL can be different than your cultural or national heritage, and then an example where they are both the same thing.

Let’s say your family is from Mexico, and you grew up speaking Spanish but not very well. In this case, you would be a Mexican Spanish heritage speaker.

Pretty simple, right?

But your family is from the Yucatán, so your traditions are totally different than los Norteños who you went to school with. You don’t wear cowboy hats or boots, the food your grandmother made is different, you never grew up on a farm, and even your Mexican Spanish dialect is different.

You might identify as a Mexican Spanish heritage speaker but as a person of Maya or Yucateca heritage.

However, both groups in this example (los Norteños y los Yucatecos) may want to relearn Spanish using the same tools, despite their cultural difference.

And a second example.

Your family is from a large Chinese city.

You grew up there for the first few years of your life, but at age 4 moved to the US. Your family celebrates all of the same traditions as everyone in your American community does, and you all identify as Chinese American.

But some of your friends speak Mandarin, some speak Cantonese, and you speak Shanghainese.

So even though all three of you identify as people with the same (or very similar) cultural heritages, you are all heritage speakers of 3 different HL languages.

However, for many people, their language and culture will aline more neatly.

For example: the overwhelming majority of people who are Polish heritage language speakers also have Polish cultural heritage.

Many French Canadians who live in English-speaking areas will speak French and identify with French heritage--not with English or Canadian heritage as a whole.

So while heritage languages and cultural heritage may seem linked, they are not always.

Learn more with some academic papers on the differences in heritages languages and cultural heritages:

3. What’s the difference between heritage languages and native languages?

Above we went through several definitions for what a heritage speaker could be.

Well, the definition for a native speaker has about just as many nuances.

Some linguists even think it’s a problematic term because of how overly-broad or extremely limited it can be.

Let’s look at how we define a native speaker first, so we can then contrast that with the heritage language speaker definitions we already went over.

First, the most broadly accepted definition of a native speaker is someone who is born and raised in a country where the language is spoken, who speaks it as their first language, and is then educated in that language.

First, the most broadly accepted definition of a native speaker is someone who is born and raised in a country where the language is spoken, who speaks it as their first language, and is then educated in that language.

There really isn’t any situation in which these people would be considered heritage speakers of that language, although they could have an additional language in their life which is their HL.

Another largely accepted definition os a native speaker is someone who is born in and raised into a community where a language is spoken and uses the language as their primary day-to-day language with family or in society.

This definition is great because without making formal education a criteria, so it can enfranchise people who speak minoritized languages.

For example, Catalan is a language spoken in the north of Spain by millions of people, but under the Spanish dictator Franco it was illegal to run a school in Catalan. So despite a thousand years of literature, poetry, and everyday use--there were several generations of children who spoke Catalan at home, with their friends, and in shops… but had to go to school in the Spanish language.

So many of the children who grew up during that time period were certainly native speakers, even if they weren’t schooled in the language.

However, some of their neighbors may have given into fascist violence from that epoche. So if the family stopped speaking Catalan with their kids, and the kids only understood parts of the language or today as adults can’t fully use it, they may consider themselves heritage speakers.

Even though they grew up in virtually the same conditions.

A third definition is based on function. In this definition, the native language of the person is not their first language--it’s simply the language that they are most competent in.

So let’s imagine a child that was adopted from another country into the US at the age of 7 by a family from outside their culture.

This child spoke their first language until the age of 7, but once they integrated into American life had no contact with their first language or their heritage culture. They forgot all of (or most of) the language, and are now functionally monolingual in English.

That child may find it useful, or even essential, to regard English as their native language. Even if it’s not their first language.

The mother tongue definition is the least tied to function. According to the Canadian census, this definition means a person’s native language is the language spoken at home by their family which they could understand as a child. This native language does not have to be their dominant language--just the original language of their home life.

They don’t even necessarily have to be able to read and write in it.

Let’s look back at the above examples of the adopted child who forgot their mother tongue and the Catalan speakers who can speak it weakly. Both of these speakers could say that the language they spoke as a baby is their native language if they chose to.

The final definition to mention is that it is widely accepted that individuals may have more than one native language.

For example, the Catalan speaker and the adopted child might both say they have two native languages, even though the Catalan speaker is a bilingual adult and the adopted child is a monolingual adult.

(And the Catalan child had two languages develop at the same time, whereas the adopted child learned one and then the other.)

So what’s the difference between heritage languages and native languages?

There isn’t a clear distinction.

But if you’re a heritage language speaker, you should now be able to form a personal opinion. (And many progressive linguists agree that speakers have the right to decide for themselves what their native and heritage languages are within these definitions.)

And are there heritage language speakers whose HL is absolutely NOT their NL?

Absolutely.

In the above definitions of heritage speakers, the broad definition groups (community-based and ancestral language speakers, as I put it in my video) do not speak their HL as their native language.

Additionally, there are heritage users who may not want to label their HL as their NL because of stigma or personal identities.

For example, a child who grew up in a Russian family a young bilingual but is a functionally monolingual adult may not want to draw attention to their inability now, or may simply not identify as Russian during this part of their life.

So in short, heritage languages can be native languages, and native languages can be heritage languages, but they are not always.

Learn more about definitions of native speakers:

- Who Is An Ideal Native Speaker?!

-

Native-Speakerism and the Betrayal of the Native Speaker Teaching Professional

- The Native Speaker: An Achievable Model?

4. Why do people forget their heritage languages?

What an awesome question.

In fact, I have a whole great YouTube video on it.

5. Are heritage language speakers bilingual?

You’ve probably guessed the answer by now.

It depends on your definition of bilingual.

There are two great poles of “bilingualism”, although there are infinite classifications inside of those poles.

- “Balanced bilingual”, formerly known as a “true bilingual”. These are the bilinguals who, as described back in 1932, were classified as having “equal” or “native-like control” in two languages. We now understand that not only are balanced bilinguals relatively rare but that even in the most ideal cases the definition is incomplete.

- “Passive bilingual”, someone who has at least some ability in the reading OR speaking OR listening OR writing in a language. Again, this definition needs additional classifications, since it groups in both children who have been bilingual since birth but lack skills in one language with someone who took a semester of French in school and still understands a few things here or there.

So now that we’ve seen how those definitions are incomplete, let’s look at some other definitions of bilingual” in order to see if all HL speakers are bilingual and if bilinguals must also be heritage language users.

- Definitions based on the age of acquisition. “Consecutive bilinguals” are bilinguals since very early childhood (maybe even from under 6 months old) and “sequential bilinguals” are bilinguals who learn one language and then the other. However, terms like “early bilingual” and “late bilingual” add another dimension. An “early bilingual” may have learned their second language at age 3 or 6, but depending on the definition be considered “consecutive” or “sequential”. A “late bilingual”, who is almost certainly “consecutive”, might be someone who gained their second language at age 13 or 63.

- Definitions based on the context of acquisition. A “natural bilingual” learned through immersion, an “ascribed bilingual” might be a “school bilingual”, and an “achieved bilingual” could be a “school bilingual” but also a “cultural bilingual”.

- Definitions based on cognitive processes. Did you know that bilinguals organize language differently in their brains than monolinguals? A “coordinated bilingual” maps their words or grammar onto a specific image, action, or trigger. (For example, hearing “el té” they see an image of a teacup or think of drinking tea.) A “subordinate bilingual” has one language mapped onto the other. (For example, hearing “el té” they think of “the tea”. In this case, Spanish being mapped onto English.)

- Definitions based on functional ability. A “receptive bilingual” or “passive bilingual” can understand two or more languages. A “functional bilingual” is closer to that definition of “balanced bilingual”, but might fall short.

- Definitions based on culture or tradition. An “endogenous bilingual” is someone who uses their mother tongue inside their community, but whose schools do not teach in that language. An “exogenous bilingual” might be similar or even the same--someone who is forced to use a colonial or political language in society. A “bicultural bilingual” also has two or more cultures present in their life, while a “monocultural bilingual” has two or more languages but only one culture”.

There are many more classifications or subdefinitions than this.

But this should give you some idea of how wide these definitions are.

So not all heritage language speakers are bilingual, as with the examples of the “community members” or “inheritance motivated” as mentioned in the above video.

And not all bilinguals are heritage language speakers, as with sequential bilinguals, ascribed bilinguals, exogenous bilinguals, and others.

But yes, you can be both a heritage language speaker (or even a student) and bilingual.

Read more about various definitions of bilingualism.

- Definitions of bilingualism and their applications to Japanese society

- Defining bilingualism

- Are you bilingual?

6. What is heritage language acquisition?

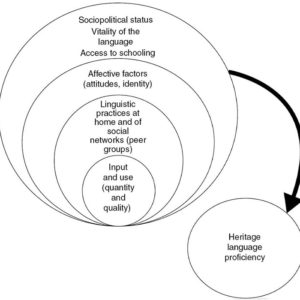

While some heritage speakers may have acquired the language in a home setting enough to communicate with family members, there are other factors that would deem the speaker as “proficient”. [source]

The first way you could acquire the HL is as a child, just as you would acquire any language easily in your life. The second way is by choosing to learn it as an older teenager or adult.

Let’s look into what that means and why it’s important.

Heritage language acquisition as a child takes place like any other early language learning. You are constantly surrounded by the language and because of a need to communicate with those around you, you eventually start making sounds that become words that become sentences.

Some heritage speakers also receive schooling in their HL as children, either for a short period of time or as occasionally throughout their childhood. This helps them learn skills like reading and writing; cultural context; and using complex grammar.

The most important thing is that this is done in the context of their home during the “critical period” (from birth until the age of 12 or so).

Then there are people who try to learn or relearn their heritage language as an adult.

Unfortunately, there isn’t much research being done on this type of heritage language acquisition.

Generally, academic research focuses on (1) institutions that teach children their HL while they’re still in that critical period or (2) help young adult speakers (age 18-22) improve their HL in a university environment.

To help fill those gaps in research, we’ve created this website.

Follow us on YouTube or subscribe to the email list to get a once-monthly summary of everything we’ve learned, found, produced, or created during that month about heritage language acquisition.

Learn more about heritage language acquisition in institutions:

- Bilingualism, HL learners, and SLA research: opportunities lost or seized?

- HLs: in the “wild” and in the classroom

7. Is it hard to relearn or improve a heritage language?

Here are a few factors that might make your heritage language hard to relearn:

- Instruction methods meant for second language speakers (and not heritage speakers)

- Bad teaching methods or negative experiences with a teacher

- Reliance on apps with little real-world context

- Lack of clear motivation

- Guilt, anxiety, or shame

- Little or no support system

And here are some factors that might make relearning or improving an HL easy:

- Programs and resources made specifically for heritage learners

- Positive and supportive teachers, either in a classroom or privately

- Integration of the language into your everyday life

- A variety of motivation and realistic goals

- Language education tools that address negative feelings or past experiences

- A community of support

I’ve written three articles on this website about how you can relearn a language, but in reality, this is the topic of a much longer book or educational program.

8. Is there special training for heritage language teachers?

Unfortunately, there isn’t any united or recognized training program for professors, teachers, or tutors to help HL speakers relearn their language.

There are some books and some lesson plans floating around online, but most of the research being done to aid HL teachers simply judge the current practices to decide what is working or not working. There is almost nothing that shows teachers how to implement those studies, and there certainly aren’t any step-by-step methods.

If you are an educator, this website is currently working on compiling more resources to help you help your student.

But until then, we suggest contacting local universities who train language teachers to see if they have any programs, workshops, or training available.

9. Where can I find a heritage language program?

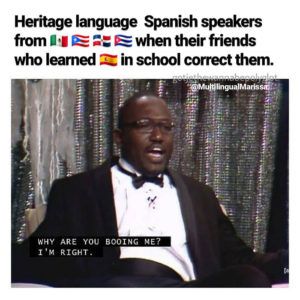

It’s also worth noting that heritage language speakers may fluently speak a non-dominant version of the language which institutionalized speakers of the language may judge as incorrect. (Also, we love memes. This one is from @multilingualmarissa on Insta)

For independent adult learners, this website exists to give you all of the information that’s out there about how to relearn a language in a practical and fun way.

As we continue to do our own original research and publish, you can learn here for free. And if you subscribe to our email list, you’ll get a once-a-month summary of everything we’ve learned or created during that month.

However, if you’re looking for an institution you can join for classes and group learning, there are generally two places where you can find programs specific to heritage learners.

- Universities may have HL programs aimed for semi-competent speakers of the languages. However, for speakers who have lost their abilities to produce the language, you’ll likely be put into a larger class for second language learners who have no contact with the languages. Secondly, these programs are often only limited to languages that have large populations in the local area as well as international prestige, such as Spanish or French.

- Supplementary programs exist within communities. They normally look like Saturday schools or language nests for children, but many will offer additional adult activities to involve the whole community in language education. These are less limited by population constraints than university programs, so they can be found in indigenous languages; historically minoritized languages; or languages that belong to a very small local community. However, many of the teachers are volunteers and many activities already assume some use of the language as an adult.

Unfortunately, there are few directories for such programs, and those that exist tend to be out of date and incomplete.

Do you want to know anything else about heritage languages?

This site is full with resources for questions like:

However, if you have another question about heritage languages that you haven’t been able to find here and want answers for, leave it in the comments below so it can be addressed with time.

Hi

I am currently working on microlearning modules to inform HLL and HL Instructors about the dynamics of HLL. I have found 2 great resources for HLL at UCLA. They have a free series for teachers: http://startalk.nhlrc.ucla.edu/Default_startalk.aspx It’s a bit old (2009) but is great. Also, they have an updated (2018) version that you need to pay for ($750) for their certificate at https://nhlrc.ucla.edu/nhlrc/professional#onlineworkshops

Try them out!

Thank you so much Laura!!!!! These are awesome and I’m going to add them into this article… do you have any social media, websites, or blog I can credit you to? I appreciate the time you took to send these over 🙂