Reading in a foreign language? (Pick the PERFECT book for you!)

Years ago, when I was first starting my polyglot journey, reading in a foreign language was my dream.

I imagined reading in other languages would be easier than conversations–mostly because I was so shy to speak, but was devouring podcasts and Netflix in those languages!

But, despite all of the popular advice I’d been given, I abandoned not only the first book that I tried to read in a foreign language–but my first three.

Years later, thanks to a lot of patience and even more linguistics research, I know why that was.

And now I’m here to teach you from my mistakes so you can read confidently in any language you want.

By the end of this article, you will:

- understand the most popular myths about reading in a foreign language and

- understand important linguistics research so that

- you can go forward and pick an awesome book to read with confidence.

✏️ TO DO: Whenever you see this pencil emoji, pause to write down what you’re going to do for that step. That way, you can follow the article along step-by-step and leave with a custom plan.

Beware of Bad Reading Advice

After years of frustration, my love for reading in foreign languages is now my absolute favorite thing to do in my free time. Here’s my favorite French literature anthology from Louisiana, which I bought during a trip to New Orleans. (And yes, I was able to speak with native French speakers from the region!)

Like I said in the introduction, my first attempts in reading in Spanish (and later French) were so bad I was constantly quitting books.

I thought the problems was just me. After all, everyone else seemed to be doing it fine!

Before we get into anything else, I suspect you’ve also already gotten some advice (or at least seen some videos) on how to read in a foreign language.

But if you’re frustrated?

You’re not alone.

So when I first started seriously researching the best way to read in other languages, I took all of the advice I was given and experimented with it. But nothing worked.

Why was that?

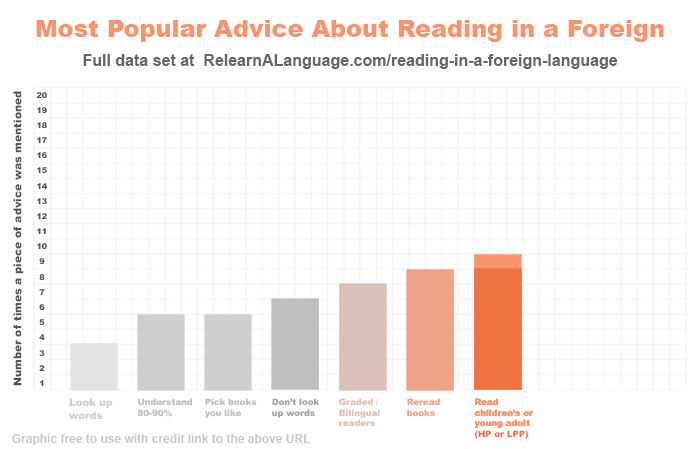

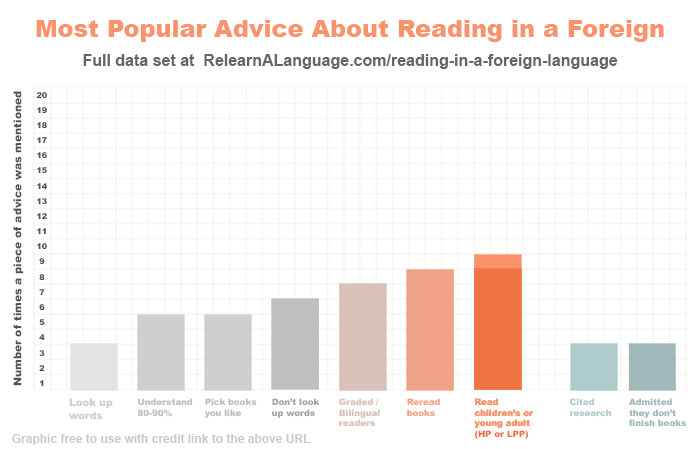

To quantify exactly what advice was being given to new language learners, I decided to watch the 20 most viewed videos on YouTube under the keywords “how to read in a foreign language” and record the results.

- I wrote down every single piece of advice that was given over these videos

- If a single creator had multiple videos under those keywords, I only used the highest-ranking video by that creator. (Ie: if someone had two videos, one with 5k views and one with 12k views, I only used the 12k one.)

- I excluded non-native YouTube content (ie: academic talks sponsored by universities)

After that, I charted any piece of advice given more than three times. Here it is:

So let’s look at these pieces of popular advice points one by one.

Look up words as you read (mentioned 3 times)

Okay, makes sense. And surely that’s everyone’s instinct anyway, right?

Understand 80-90% of what you read (mentioned 5 times)

That 80-90% was mentioned over and over, so I thought it was worth noting. Seems specific!

Pick books you like (mentioned 5 times)

Again: this should be common sense, right?

Don’t look up words (mentioned 6 times)

At this point, I realized why I had been so confused when I tried to read in Spanish and French.

A lot of the advice out there was openly contradicting itself.

Use graded or bilingual readers (7 times)

These are books written specifically for language learners or written with the target language on the left and English on the right.

This advice seemed to be like the only one that so far was based in anything real–teachers had recommended these things to me, and I can agree from my own experience that they’re super helpful.

Reread books you’ve already read in your native language (8 times)

Again–these seemed like really random advice. Why? Wouldn’t I get bored?

Read children’s books (mentioned 9 times: 8 of those instances being specifically Harry Potter or Le Petit Prince)

At this point, the argument fell apart.

The most popular advice was to read two books that, unless you’re studying English or French, have nothing to do with your language goals or even the culture that the language comes from.

So after reading this, I decided to go back to those videos to gather two more data points:

And here we have it.

3 of the video creators cited research.

But another 3 admitted themselves they also didn’t finish books in the languages they’re studying.

The rest were silent about where they got this advice from, or what their actual reading abilities in that language are.

So my next question was…

Is this advice working for people?

What problems are other language learners having when trying to read in another language?

Was I alone in how frustrating I found it?

The Hardest Parts of Reading in a Foreign Language

Because I’m a data junkie, I did another quick survey–this one came from language learners on my Instagram who are all at least good enough at languages to follow my language meme account.

A few things to know about this data:

- It was collected in August 2020

- Most participants studied languages for fun, and many indicated they spoke or studied more than 2

- They were asked to do the survey for one target language only

- They reported to be between A1 – C2 in that language, but about 50% were at the B level (intermediate)

- You can see the full data from this survey here.

Now, let’s see if the advice being given online is solving these language learner’s problems.

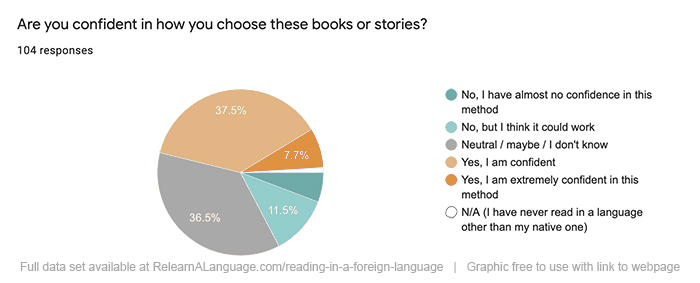

So out of the questions that I asked about strategies, this was the one language learners reported that they struggled with the most: picking out a book.

Over half of them reported that they are not confident or neutral in how they pick up books.

Considering the popular advice is to reread books, pick books that you like, or read Harry Potter or Le Petit Prince… this wasn’t shocking to me.

But in theory, people are still picking out books and starting them, right?

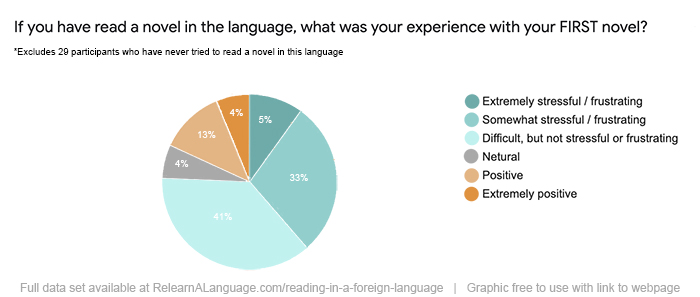

So how does reading go for them when they pick up that first book in a new language?

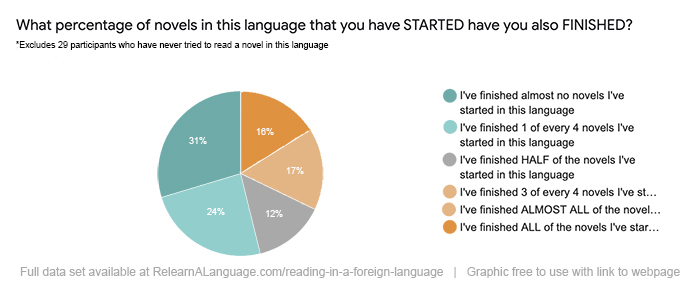

Well, this isn’t exactly great news.

Despite the popularity of reading in a foreign language, as well as the abundance of advice… nearly 75% of people said their first book was difficult, stressful, or extremely stressful!

But hey, language learning is like that.

And as long as we’re making progress, what’s a little stress?

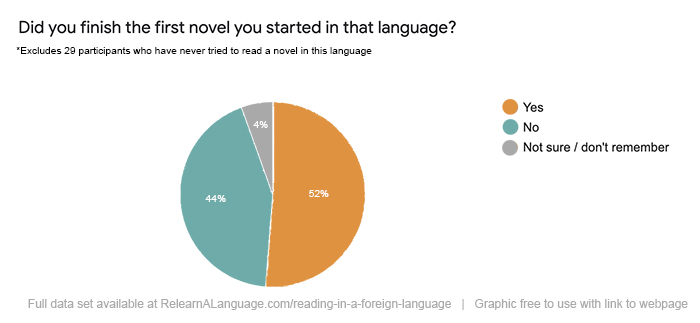

So, are language learners making progress with reading?

Well…. maybe not.

Sure some people get through the difficulty or stress to finish that novel, but nearly half don’t (or don’t remember).

But that’s just the first novel, right?

Again–learning another language is full of stress and mistakes!

So are people learning from their mistakes and becoming better readers?

This isn’t exactly uplifting.

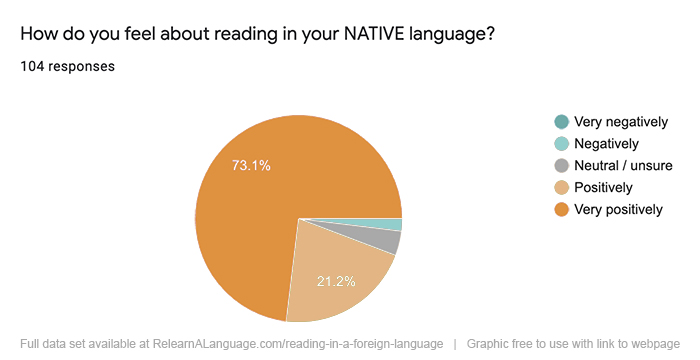

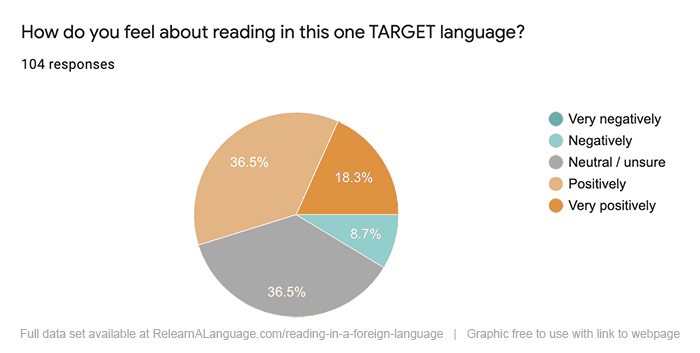

But finally, I asked–maybe it’s just because we prefer to learn languages, and don’t feel great about reading.

Maybe book-lovers and language-learners are two different sets of people?

So… what gives?

Well, the survey also had a section where people could discuss their biggest frustrations in reading in another language.

Because they typed whatever they wanted, I couldn’t make a chart. But here were a few responses that stood out:

- Not knowing words or needing to look up words (or something about vocabulary) was by far the most frustrating, mentioned in over half of all responses

- Modern slang or outdated grammar were the next most often menioned

- Finally, people complained about not being able to find books they liked at their level

So what’s my big take away from all of this?

Not only is the reading advice online not helping… it’s often not even addressing these problems.

Now, let’s look at some real linguistics research that is.

✏️ TO DO: On a piece of paper, write down what has frustrated you about reading in your language in the past. (If you’ve never tried to read in this language, don’t worry–you can leave your paper blank for now.)

The 98% Reading Rule

To look up or not look up? That’s the question!

Popular polyglots seem to be split on the idea, but neither of those pieces of advice seems to be helping.

It’s still the biggest frustration when reading in a foreign language!

But I mean, according to that advice we should be able to understand the text if we understand 80-90% right?

So why is everyone frustrated in the first place?

Well, in 2000 two linguists did a study. Here’s what they did:

- Participants were given a difficult text to read

- Participants had no access to pen, paper, or dictionaries

- Researchers first determined how many words in the text were unknown to each participant

- Participants then had to answer a series of questions about the text

So what did they find out about vocabulary and reading comprehension?

Participants who understood less than 98% of all printed words were not able to demonstrate that they understood the text, even when they thought they understood it. [Hu & Nation, 2000]

So that 80-90%?

That’s linguistically bad reading advice.

Sure, at 80-98% comprehension you can use tools like a dictionary, note-taking, or help from a teacher.

But if you’re not looking up words, you’re not going to understand the text. You’re going to get bored and frustrated.

Plus–at 80% comprehension, you’re looking up 1 out of ever 5 words just to understand the text!

Now, 98% doesn’t mean easy. There might still be slang, weird grammar, or phrases you don’t understand.

But you’ll be able to understand the plot or main argument of the text without constantly looking up new words.

And it’s going to make all the difference.

How to find text that’s at 98% comprehension

First, you’re going to want to cast a wide net.

We’re going to start with a few different genres of text, and look at about how many different words they tend to use per text.

- Textbooks that have large paragraphs or dialogues for students to read tend to include around 3000 different words over the course of the book.

- Graded readers or bilingual books for students tend to include 5,000-6,000 different words per book

- Newspapers, magazines, and short stories made for native readers tend to use the same 7,000 words across multiple stories or issues

- Simple novels for natives (the kind you read in high school under 200 pages) normally have the same 9,000 words throughout the book

- Full adult novels (think something 400-700 pages and very contemporary) have about 9,000 different words

To start, that’s a lot of words. I know.

But don’t worry, because you likely know a lot more words than you know.

Here’s a general idea of how many words you know at various skill abilities in the language.

- If you were dropped in a foreign country, could you survive asking for food, shelter, the airport, and a glass of wine? You’re probably around 3,000 words. (You’re still at large texts within textbooks, but that’s a great starting place.)

- Can you have an ok conversation, even if you have to stutter and mime a bit? You’re probably at 5,000-6,000 words. (Aka, a graded reader or bilingual book.)

- Do you consider yourself fluent? You probably have around 7,000 words–enough to read a newspaper, magazine, or short story in the language.

- Have you already read in another language? Have you been fluent for a while? Congrats–you’re likely at around 9,000 words and a short novel might be at your 98%.

- And finally, have you lived in a country where this language is spoken and worked there? You’re likely at around 15,000+ words–enough to read a full novel.

Now, there are some other ways to guess your vocabulary in another language.

For English, there are tests online. There are also apps like Anki or Lingq. And then there’s the CEFR.

But unfortunately, none of them are ideal. Those above estimates are based on some linguistics research about grade inflation and the CEFR, so they’re likely your best best.

(And don’t worry–what you need right now is an estimate, not a perfect number.)

✏️ TO DO: On your paper, right down what you think your estimated vocabulary is and what genre of text you want to start with.

How to find your first book to read in your target language

Now that you have your literary genre, we need to find the next most important thing:

Your 98%.

To do that, you can follow a simple formula:

- Pick the first page and count the number of words. Just multiply the number of words on one line times the number of lines.

- Count the new words on that page by going through and counting one by one.

- New words ÷ Total words = Percentage of new words

- Make sure your percentage is 98%, and you’ll be golden!

It might take a second to find a book or resource you want to read, but this step will save you a TON of work and frustration going forward!

Want to see my personal reading lists in French and Spanish? Click the images below to open up those articles where you can see not only some awesome books but language notes and links to the first pages!

By now, you should have an understanding of how to confidently pick out a book that is at your reading level.

But remember: it’s only fun to read if you’re motivated!

So take your own personal tastes and interests into account.

There’s no use starting on some philosophical French book if you never read those in your native language, or some beautiful Japanese poetry when you really just want to read manga.

Go forward, and have fun!

Next, we’ll talk about strategies for reading in a foreign language when you understand 98% of what’s going on, but still can’t seem to sit down and finish reading a book.

✏️ TO DO: Write down where you want to start looking for your first text to read. (If you want to use my French or Spanish lists, you can also take a few minutes right now to pick out your first text!)

Establish Your Reading Space

My bedroom is my ideal reading space: it’s lined with bookshelves, has a ton of pillows, and even has soundproofing to keep out noises. (You can see it in some of my YouTube videos!)

Now vocabulary aside, a lot of people have found reading in a foreign language boring, frustrating, or just not fun.

Hopefully, if you can follow the plot and you get to choose what you read that won’t be a problem.

But what happens when you can’t pick your own books? When you have to read something for homework?

Or if you like your book…. but you can’t put down social media?

The problem you’re having if you understand and like a book but can’t concentrate is probably a lack of dopamine.

Dopamine is our reward chemical.

Let’s do a quick exercise so you see what I’m saying.

Imagine you’re walking into a restaurant when you see a text message from someone you really like. (Seriously: imagine how great that feels.)

Now imagine that you find $20 in the parking lot on your way in.

Finally, imagine hanging out with your friend and laughing over your favorite food.

Those are all examples of dopamine.

Dopamine rewards us for doing something gratifying. For when we win or get a treat. For when we laugh.

But here’s the thing.

Reading doesn’t give us dopamine.

What might?

Checking social media. Scrolling on social media.

Cleaning up a bit. Making a snack.

So your brain could be sabotaging you because, let’s face it, reading is hard. And our brains are wired the same as they were 20,000 years ago – we don’t want hard work, we want to win and snack and make friends!

This is something psychologists who work with kids know all too well–especially if they work with kids or adults who have ADHD, who’s bodies crave that dopamine many times harder than a neurotypical person might!

So here are the common dopamine pitfalls we need to avoid?

- Social media (and screens in general)

- Talking to someone we live with

- Someone we live with coming in and interrupting us

- Constantly getting up for drinks or snacks

- Procrastinating by doing small tasks (such as cleaning or making lists)

- Constantly rearranging our workspace

- Adding or removing clothing for temperature regulation

And the list goes on.

So if you find yourself engaging in these tiny tasks, you need to plan ahead.

✏️ TO DO: Write or draw your ideal reading space. What does it look like? Then decide: how long will your reading sessions be for? What will you do before them? What can wait to be done until after they’re over?

4 Strategies for Reading in a Foreign Language (When Vocabulary Isn’t the Problem

Now, we’re left with one more recurring problem: when we understand the words individually…. but not in a sentence.

Maybe the culprit is slang, or obsolete grammar, or just too much information.

There isn’t any single magic reading in a foreign language strategy.

But here are 4 different reading strategies for organizing your information as you read.

This way, you can follow the plot or argument more easily and focus on the language itself.

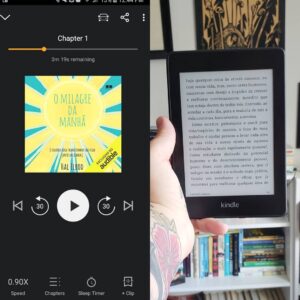

I started reading in Portuguese with a translation of the Miracle Morning. (Self-help books are written at really low levels, and are often super fun.) To stop myself from skimming and to familiarize myself with the language, I used an audiobook to read alongside with.

1. Checking-In / Slowing Down

Checkin-in is a skill we likely have if we can read books in our native language.

When we realize we didn’t understand something (or maybe are spacing out) it’s easy to stop and go back. We simply reread.

But as language learners, we’re used to a certain level of ambiguity.

In fact, tolerating some vagueness when we’re listening or reading is often essential to not totally losing our minds!

But when we keep barreling ahead with a text, despite not understanding it, we’re doing a disservice to ourselves.

Here’s a few ways you can slow down and make sure you actually understand what you’re reading.

- Check-in as you’re reading

- Find the key sentence in every paragraph and the main sentence in every section

- Summarize every paragraph in your head

- Check-in after reading

- Write a summary of what you just read per paragraph, page, or section

And what if you still don’t understand what you read?

-

- Break up your summaries into smaller parts

- If you couldn’t summarize a page, try summarizing every paragraph

- If you couldn’t summarize a paragraph, try summarizing every sentence

- Break up your summaries into smaller parts

- Find the paragraph, sentence, or word that caused the problem

- Look up words or even translate the whole paragraph (it’s not cheating)

But you can only likely do this all if you read slowly. So here’s how to stop and slow yourself down if you’re flying by so quickly, you don’t realize you’re lost until it’s too late.

- Using the check-in strategy on its own will naturally help

- But also make sure you have plenty of time to read…

- …before deadlines.

- …in designated reading time.

And if that’s still not working? You can force yourself to read slower by:

- Reading out loud to yourself

- Reading the words on the page as an audiobook reads them to you

Now these reading strategies might feel counter-productive. After all, the goal is to read faster–not slower. Right?

But once you get good at these consciously-selected strategies, they will become unconscious skills.

You will naturally get faster at reading, just like in your own native language, because you’ll be getting better at it.

So don’t worry–you can trust this process. (It’s backed by science!)

✏️ TO DO: Which of these strategies to check-in or slow-down do you want to commit to using? Write it down.

2. Annotate while reading

I first used annotating to get through 100 Años de Soledad. This was before I knew about the 98% rule! But it was a great learning lesson, and I still love to write new words directly into books when reading.

Annotating is the easiest of these reading strategies, and you might already be doing it!

Basically, annotating is taking notes in-line with the text.

Here are a few ways you could annotate for vocabulary and sentence structure:

- Underlining problematic vocabulary and writing the definition right on the page

- Underlining anything you don’t understand so a teacher can help you later

Since studies have shown that without looking up words as you read you’re likely to only remember 1% of new words [Hu & Nation, 2000] this is an awesome way to learn a language by reading.

And here’s how you can annotate for the overall concept (when you understand the words, but not the meaning)

- Underlining the key sentence of every paragraph

- Summarizing every paragraph in 2-3 words in the margin

- Noting literary language: symbolism, hyperbole, and anything else that’s not part of the actual story but somehow important

- Clarifying flashbacks or dream sequences (or anything else that’s not related to the main plot)

- Writing down timelines, points of view, or locations

- Noting arguments for or against the main point

I find annotating is amazing for non-fiction (and in my opinion, essential) but it can be great for novels with complicated plots too.

3. Mind mapping your reading

Mind mapping is an amazing skill–I use it all the time when brainstorming blogs or YouTube videos!

But here’s how you can use it to keep track of a long and rambling piece of writing.

- In the center of a large piece of paper, write the name of the book

- As you encounter points that seem central to the argument, add them on “arms” spiraling out

- Add subpoints after that

- Hit a dead end? You can always re-copy your mind map onto a new page and restructure with your new (and better) understanding of the book)

- For an extra challenge, do this all in the target language

This is honestly probably the best way to take notes on reading in a foreign language when you have to present to a class or write about it later. Not only will your reading be more clear, but you’ll be able to easily come back and summarize or explain later.

4. Make concept cards for characters

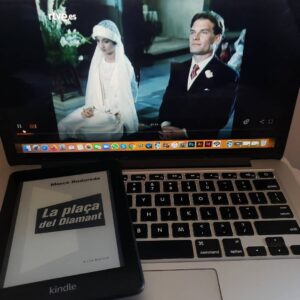

I read in different languages, so I’d say I’m confident in a lot of my strategies. But when I first started reading this Catalan classic, I couldn’t keep track of the characters! When I found this old TV adaptation of it, I realized it was because of how many nicknames everyone had. (And that’s how I started using concept cards myself.)

Concept cards were a game-changer for me when reading in French.

I found that I was so focused on all of this new information, that my brain was simply skipping on the details!

I wasn’t paying attention to the characters at all, so kept getting confused and frustrated.

Here’s how to use concept cards for reading in a foreign language:

- Get a series of 10-20 cards, either cut out from paper or note cards

- For the first 1/3 of the book, give every character their own card with their name on the front

- So if your first 3 characters are Chéri, Léa, and Charlotte, they will each have their own card (3 cards total)

- The first 1/3 of the book is when any reoccurring character might occur, but you never know who might show up again so I suggest making them for anyone with a name (or even someone important without a name)

- On the back of each card, write notes in the target language about that character

- On each card, you might want to write full names or nicknames, adjectives, or their relationships to other characters

- I suggest note-taking in the target language to keep your brain in the reading space!

- Refer back to these cards if you need!

This sounds silly–after all, you don’t need to do this in your native language, right?

But I’m telling you: these changed the game for me.

As a bonus, you can also use the cards as adjective flashcards! For example, if your front says “Charlotte”, you can use them as flashcards to remember new adjectives in the target language, just like you would a normal flashcard.

✏️ TO DO: Which of these three note-taking methods do you want to try for the next book you’re going to read? Write it down on a sticky note which you can use as a bookmark to remind yourself of this!

Recap: The 4 Main Steps for Reading in a Foreign Language

Now, to recap, here are the four things you should be able to do at the end of this article:

- Understand your vocabulary level in the language

- Start looking through sources you enjoy for your next read

- Establish your reading space

- Use any additional reading strategies you need

If you’re not sure about any of these, go back to the section where they were and reread.

That’s because if one of these parts breaks down, the whole thing might not come together and your reading might be just as frustrating as before.

But that said, I wish you all the best reading your next book!

If you have any questions, feel free to leave them in the comments for me. I plan on creating a ton of content around reading in a foreign language, including tons of YouTube videos and likely more blog posts, so I’ll hopefully get around to answering everything that I can!

Want to learn more about foreign language reading strategies? (Bibliography)

Here’s the full bibliography for everything I cited in writing this article.

I’ll warn you: these are largely academic books and sources which aren’t written for language learners. In fact, 95% of the preparation for this article was translating these studies into actionable steps for language learners!

But if you’re interested, here you go:

|

Amen, Daniel G. Healing ADD from the inside out: the Breakthrough Program That Allows You to See and Heal the Seven Types of Attention Deficit Disorder. Berkley Books, 2013.

|

|

Arguelles, Alexander, Reading Literature in Foreign Languages: Tool, Techniques, Target, Polyglot Conference, (Oct 14, 2014),https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PUqME-RTtIs

|

|

Buzan, Tony. Mind Map Mastery: the Complete Guide to Learning and Using the Most Powerful Thinking Tool in the Universe. Watkins, 2018.

|

|

García Santa-Cecilia, Álvaro. “Plan Curricular Del Instituto Cervantes Niveles De Referencia Para El Español.” Instituto Cervantes De Madrid, 2006, cvc.cervantes.es/ensenanza/biblioteca_ele/publicaciones_centros/PDF/berlin_2008/03_garcia.pdf.

|

|

Hu, Marcella & Nation, Paul. (2000). Unknown Vocabulary Density and Reading Comprehension. Reading in a Foreign Language. 13.

|

|

Iverson, Niels, Vocabulary acquisition – wordlists and the role of context, Polyglot Conference, (Oct 22, 2014), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vzruvBlLE7I

|

|

Krashen, S.D. (1985), The Input Hypothesis: Issues and Implications, New York: Longman

|

|

Milton, James & Alexiou, Thomaï. (2009). Vocabulary size and the common European framework of reference for languages. 10.1057/9780230242258.

|

|

Neagu, Carmen. (2020). INTENSIVE VS. EXTENSIVE APPROACHES IN FOREIGN LANGUAGE TEACHING. 10.13140/RG.2.2.15879.83366.

|

|

Paris, S. G., Wasik, B.A., & Turner, J.C. (1991). The development of strategic readers. In R. Barr, M. Kamil, P. Mosenthal, & P.D. Pearson (Eds.), Handbook of reading research, Vol. 2 (pp. 609-640). New York: Longman.

|

Very interesting analysis! I enjoyed your talk, today. Thank you for putting this together. Your comparison of the advice, and use of research to correct is very helpful.

I love reading in my native language, and it has been my primary and favorite method for expanding my native English vocabulary. I can barely tolerate flashcards, and scored well on standardized exams by doing practice exams and by being very deliberate about looking up and recording new words from books that I read or shows that I watched. Surprisingly many of the words from science fiction novels (obsequious) and episodes of Murder She Wrote (that unctuous gentleman) were on the exam.

My goal for reading is to become familiar with grammar and vocabulary in their most natural usage. My target language is Finnish. I used graded readers when learning to read in English, and I am a huge fan, but have trouble finding good ones for foreign languages. I have been trying to read some of the same books in my target language for two years. I finished half of a teach yourself textbook, one textbook from Hippocrene that was predominantly stories, and one graded reader. Children’s books can have very difficult vocabulary and so aren’t great for A1 or A2. I found beginner lever material meant for immigrants from the country of my target language.

Regarding dopamine, it really sped up my progress to clarify my goals, and not worry about comprehension. Because my target language uses declensions my first lesson was just to get used to recognizing words I know in different cases. Each book is meant to be read more than once! Underlining and writing in the book has been amazing. Reading work is a success if I read a story and learn one word, and get used to recognizing words that I know in different forms. Looking up every word is demotivating when you understand less than 90%. So, I’ve been using resources like Readlang and native speakers (family member, iTalki teacher) to be my insta-dictionary to help me get through texts faster and have more fun. Sometimes I will read aloud also, asking a native speaker to correct me, and I underline diphthongs, syllables, and words that I mis-pronounce. I’ve also been copying YouTube transcripts to Readlang to alternate practicing listening and reading the same material.

The hardest part is filtering from all that I don’t know to identify structures or vocabulary that are worth studying from a grammar book or text book. I think a textbook is a good reference for that. Also, if I wanted to rewrite in my own words as generally as fits my current knowledge, what would I need?

I’ve really gone back to the techniques I used as a child to read: memorizing text, reading them repeatedly, and not understanding half of what’s being said. I think these techniques are supported by research at least for learning to read (not foreign language). As a child, adults would talk or read aloud and I understood only a few words or points of what they were talking about. Comprehension is relative. 🙂

This was super helpful! I’ve been learning japanese and spanish, and had some trouble with finding books to read at my level. I ended up reading the magic tree house series in spanish and while this helped my spanish a bit, I already knew everything that happened in the books from reading them as a kid. 🙂 Also, the part you wrote about dopamine was helpful because I’ve been rather unmotivated in general lately- I think cutting down on things like social media will help a great deal.

Thanks Angelina! I really really love psych so I always try to make sure everything I do with languages is good science–so I’m glad the dopamine thing resonated with you!

With regards to Harry Potter or Le Petit Prince, I feel it’s an exaggeration to say that reading hundreds of pages in your target language has “nothing to do with your language goals”, even if it is (professionally) translated material.

For Chinese, I’ve read the entirety of both 玛蒂尔达 (“Matilda”, ~250 pages) and 女巫 (“The Witches”, ~230 pages) and found it beneficial, particularly in regards to reading speed and vocabulary. I consider it a decent first step. Some people use graded readers, while others prefer children’s books.

Hey! You’re right that it’s a bit of hyperbole. Someone really might have the goal of writing fantasy books in their target language, so HP or LPP might be good first starts. And I’m really glad Roald Dohl helped you with your Chinese! That particular point really came from how that was the single most common response, but I’ve met very few people who found reading those books engaging, or who were learning a language simply to improve it (and not just using those books as a stepping stone to connect with the culture in some other way.) But thanks for reading and taking the time out to leave a comment since there is no one right way to learn a language, and hopefully others who disagree with me will come down and see they’re not alone or doing something wrong 🙂