SPANISH GENDER: Masculine, Feminine, and Beyond

by Marissa Blaszko · October 27, 2021

Spanish masculine and feminine grammatical gender is often taught with a “don’t think about it too hard” attitude.

“Just memorize” noun gender as a student because “that’s just the way it is, but it’s not sexist”, right?

But if you’re a Spanish student or heritage learner (especially if you’re a woman or queer person) Spanish grammatical gender can be extremely frustrating.

Welcome to the internet's first comprehensive guide to Spanish grammatical gender beyond the masculine and feminine binary!

In this guide, you’ll get everything you need to start using Spanish gender correctly right away, but you’ll also be left with plenty of additional resources to start using Spanish grammar with gender creativity as you grow your language skills.

Because why just memorize some rules when you could explore and have fun with language learning?

Spanish Gender Master Guide

BEGINNER: Spanish Masculine & Feminine 101

Learn the beginner basics of Spanish textbook grammar.

INTERMEDIATE: Inclusive Spanish Gender

Want to know more about feminist and queer options in Spanish? We gotcha covered.

ADVANCED: Beyond the Masculine and Feminine Gender Binary

Go beyond grammar and beyond the gender binary. Perfect for intermediate or advanced students!

A quick background about me, the author and curator of this list.

I’m a queer person, Polish heritage language user, and fluent Spanish speaker. My first frustrations with translating my identity between languages and cultures were in English and Polish, but the first time I felt like I could successfully navigate those differences were between English and Spanish–despite how the Spanish masculine and feminine binary could sometimes grind me down.

This article about Spanish gender will be written for language learners and speakers for all levels, but will make a special point to address people in the Americas because of the intimate convivencia Spanish and English here.

I hope it’ll quickly help beginner Spanish students understand the concepts of grammatical gender, but then help the rest (and most curious) of us go beyond the Spanish masculine-feminine narrative.

1. Spanish Masculine and Feminine 101

First, let’s get it out of the way. The thing you’re probably searching for.

Here's the easiest explanation online so you can start identifying if a Spanish noun is masculine or feminine.

But why?

Whyyy are nouns either masculine or feminine in Spanish?

Here’s a good explanation:

If you want to learn more about the benefits that grammatical gender has for language acquisition in babies and children this research article is pretty thorough.

But where did Spanish’s grammatical gender come from? Here’s a great video that uses a bit of German as an example.

So while the Spanish masculine feminine grammatial gender construction may be annoying for those of us learning the language, they’re not as annoyingly useless as you might think!

But no matter how neutral all of those videos made grammatical gender sound…. can grammar be sexist?

2. Inclusive Spanish Gender

Now: languages are human-created things that are reflections of the living, breathing people who live in them.

So no matter what you’ve been told in class, humans established the written rules of Spanish grammar and made conscious decisions about gender. (Someone had to decide that in a group of 248098 women and 1 man, we have to use the masculine right?)

Now: are you interested in changing how you speak Spanish to promote gender equality?

Because you can!

Inclusive Spanish, sometimes known as español no sexisto, is an awesome option for Spanish language learners who want to think and speak consciously.

Here are 3 options for using inclusive Spanish gender.

Option 1: Neutral -e Endings

Swapping the normal -a or -o endings of a work for -e when referring to a group is the easiest way to neutralize your Spanish.

Here’s how it works:

On top of polite and neutral changes (again like nosotres, elles, or les amigues) the singular elle is slowly becoming adopted by media as a translation for the singular English “they” when referring to a nonbinary person.

Most notably, the New York Times and Washington Post have added elle/elles into their Spanish style guide for exactly that purpose. (Check out the third segment of this episode of El WaPo podcast for more.)

However, words like “les cocineres” or “les compañeres” aren’t in any dictionary.

So what do everyday Spanish speakers think of the change? Here are some street interviews:

So if you’re feeling confident, go for it! But depending on your level of Spanish (and who you’re speaking to), just know that you might be corrected.

Option 2: The Infamous -x Endings

Next let’s explore the term “Latinx”, as well as accompanying language features like “ellxs” (ellos/ellas).

Because while the term “Latinx” has grown in popularity over the past two decades, it has a particular stigma around it.

While around 25% “hispanics” living in the US has heard of the term Latinx, the fact that less than 3% use it [source]. It’s also used less outside of the US than it is domestically [source], so Spanish speakers of all backgrounds may push back against the term [source].

But let’s learn a bit more about why it’s worth defending in the context of Latinos, Latinas, and Latines living in the US.

If you want a well-cited history of the term, I highly suggest this paper by a professor at Florida Atlantic University.

But just know that while “Latinx” has an positive history, you may get some pretty gnarly backlash from it in public forums.

It’s also a bit clunky to pronounce, so while popular online it doesn’t seem to be gaining the same popular traction as the -e ending.

Option 3: Repeating Spanish Masculine and Feminine Together

In English, hearing a phrase like “congressmen and women” in a political speech might not be cause for a front-page headline.

But when Spain’s future president Pedro Sánchez addressed his colleagues as “miembros y miembras”, a discourse was ignited.

In English, this might sound like the equivalent of the well-worn phrase “ladies and gentlemen”.

But to the Spanish native ear, which would normally assume that women would be included in “miembros” (but not that men would be included in “miembras”), the phrase might repetitive or even provacotive.

This doubling-down on language to create a repetitive but binary-balanced sentence is your third inclusive grammar choice.

This new article contemporary to Sanchez’s 2015 address gives a lot of context for why this seemingly neutral way of speech is a relatively new way of using Spanish, and this dispatch from the Real Academia Española (the body which regulates the language within Spain) is the best official resource for why you’ll be hearing phrases like “ciudadanos y ciudadanas” more and more often.

The key takeaway? Although “todas y todos” (or “todos y todas”) is still far from the default way to address a large group, out of all 3 options this one is the one you’re most likely to hear in political speeches, academic lectures, or mainstream discourse.

Want to see some academic sources for all of this? Here are some really thorough ones:

- Guía de comunicación no sexista (Instituto Cervantes)

- Manuel de comunicación no sexista (Instituto national de las mujeres, Gobierno de México)

- Guía para el uso no sexista del lenguaje (Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona)

That concludes our exploration about gender-neutral Spanish grammar.

In the next section, we’ll talk about moving beyond both the grammatical and social gender binary.

Not sure why you’d want to keep reading? Here’s an 8 minute TEDx about the natural beauty of queerness that will inspire you (no matter what your sexuality or gender).

3. Beyond the Spanish Gender Binary

Just like the Spanish language itself, the current gender social system we have in place in the Americas was imported from Europe.

In this section, we’ll be deconstructing what that means for those of us who live in the New World socially, both as language users and wonderfully complex humans.

Just a head’s up: the topics covered in this section are total rabbit holes. I suggest bookmarking this page and making your way through the documentaries here since they’re just a few of the dozens online and you’ll likely want to watch others too!

Context: Pre-Colombian Gender

First we’ll start with a lecture by Dr. Andrés Gutiérrez Usillos, who works in El Departamento de América Precolombina in Spain’s Museo de América.

Dr. Gutiérrez Usillos’s lecture talks about nonbinary identities held by indigenous people in the Americas before European contact or contact with the Spanish language.

The most famous examples of pre-Colombian gender variation are the Muxe of Oaxaca, Mexico. Here’s a short documentary about their daily lives, but remember that an outsider perspective isn’t the full story.

Even outside of any number of genders and sexes, just how the current machista Spanish masculine feminine gender binary is constructed is a product of colonialism. (Irene Silverblatt’s book Luna, sol y brujas: géneros y clases en los Andes prehispánicos y coloniales is nearly impossible to find, but explores the anthropology of the binary before European contact.)

Resources: Spanish (Trans) Gender Language Immersion

Now, let’s get back to language.

What are the terms and concepts you’ll want to know in any language in order to talk about gender and sexuality? Here’s a great 101 for Spanish native speakers (which doubles as a great guide for language learners).

There are also a number of videos by CARKI Productions which I recommend as another great starting place for an intro to LGBT+ vocabulary.

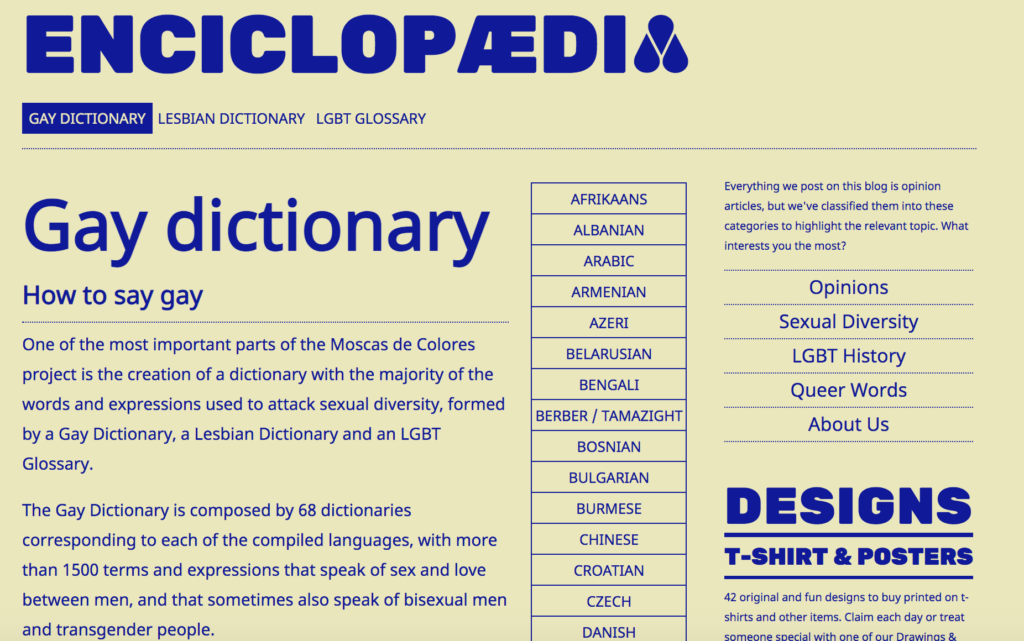

But if those videos are a little too basic for you, I highly recommend the Gay Dictionary.

The Gay Dictionary by Moscas de Colores is an English dictionary for the many ways LGBTQAI+ label themselves throughout the world and its languages.

It’s available in an impressive number of languages and translated really, really well.

YouTube, Podcasts, & Social

If you want a larger look at queerness and transness in the Spanish-speaking world, make sure you check out some new media.

▶️ YouTubers, 🎙️ Podcasters, 🎵 TikTokers:

- ▶️ Agenda Queer (Vice Español 2 part documentary)

- ▶️ Daniel Valero (Pop culture, sex, and volg)

- ▶️ PutoMikel (History, Archelogy, and plenty of drag)

- ▶️ Elsa Ruiz Cómica (Trans vlog)

- 🎙️ La Hora Trans (trans experiences an stories)

- 🎙️ Ningún chile te embona (LGBTQIA+ perspectives from Mexico)

- 🎙️ No Soy Moda (Inspiring stories about LGBTQIA+ people)

- 🎙️ Wilferland (queer politics, sociology, and culture)

- 🎵 @zatcharias (gay slang from Mexico City)

- 🎵 @vico_ortiz (NB tiktoker getting creative with inclusive language)

Books & Authors

Elsa has some great recommendations, but I would also recommend checking out the following authors:

- Chilean author and LGBT+ activist Pedro Lemebel wrote a number of works about 20th-century gay communities in South America

TV & Movies

Here are a few recommendations from actual queer people (and not just straight people write gay or trans characters).

- Valeria on Netflix (features a main character coming to terms with her sexuality)

- Drag Race Spain (streaming depends on country, but meet the queens here)

Gender queer-specific translation resources

Ártemis López is a researcher doing research on nonbinary inclusive Spanish and English-Spanish translation. Check out López’s interviews on rtve or panel interviews to learn more about this new area of translation.

(Thank you to @martinalanguagetravelling for this tip!)

And finally, because so much of our website is dedicated to heritage language users, we’ll end this section with first-hand accounts of what it’s like to be both nonbinary and Latinx in North America.

CONCLUSION: Experimenting with the Spanish gender: masculine, feminine, and beyond

Languages are living things, and they are reflective of the living people who speak them.

As a Spanish student, you yourself become part of the people who change and create the language as you speak it.

So get creative with how you express Spanish masculine, feminine, and non-binary genders.

Listen to as many gender-creative speakers as you can.

Take notes on phrases, words, and non-verbal communication that you love.

And start playing with the language!

Do you have additional resources, fun media, or helpful tips for other Spanish language students?

Leave a comment!

I’d love to hear more about what should be included in (or updated with) this article.

The goal is to create a huge bibliography for other gender creative, non-conforming, or nonbinary students–so I’d love to add more at any time!

The problem of “miembros y miembras” (in specific) is not the repetition being redundant nor just the attempt of being inclusive, but that the word “miembro” doesn’t have any feminine form at all like “ciudadano”, “todos” or most words referring to people have. A woman who is member of anything is also called a “miembro” without that implying she has this of that gender, since “miembro” refers to a single reality (something being part of anything) without telling its specific gender. In the other hand, you can say “todos y todas” because the word “todas” does exist as an possible gendered variant of “todos”. Another example that can be more clear is “portavoces y portavozas” where is grammatically “impossible” to make the word “portavoz” feminine since the word is already neutral in gender: you can only say “los y las portavoces” instead, marking the gender just with the articles (i.e. its grammatical construction tells you that someone brings [porta] a voice [voz] without giving any gender information at all). Or in the same way we also say “él es una bestia” or “ella es un genio” where the gender actually shouldn’t match, since these words don’t have any other form and can only be used with the gender they have, even if the person they refer to has a different gender.

Hey Asher! That’s certainly true, but it’s exciting to see how people are using their agency to change language. I just had a discussion the other day about how in a feminist (all women) yoga class that was a friend was attending, the teacher (who was native Argentinian) used the word “cuerpas” instead of “cuerpos”. Sure it sounded strange, but in the context of a yoga class about helping women reconnect with their bodies, why not play with language to start thinking in new ways? (And that’s the whole point of this article–to get creative and expressive!)