Who are language learners? (2021 study of dabblers, polyglots, hyperglots)

by Marissa Blaszko · March 10, 2021

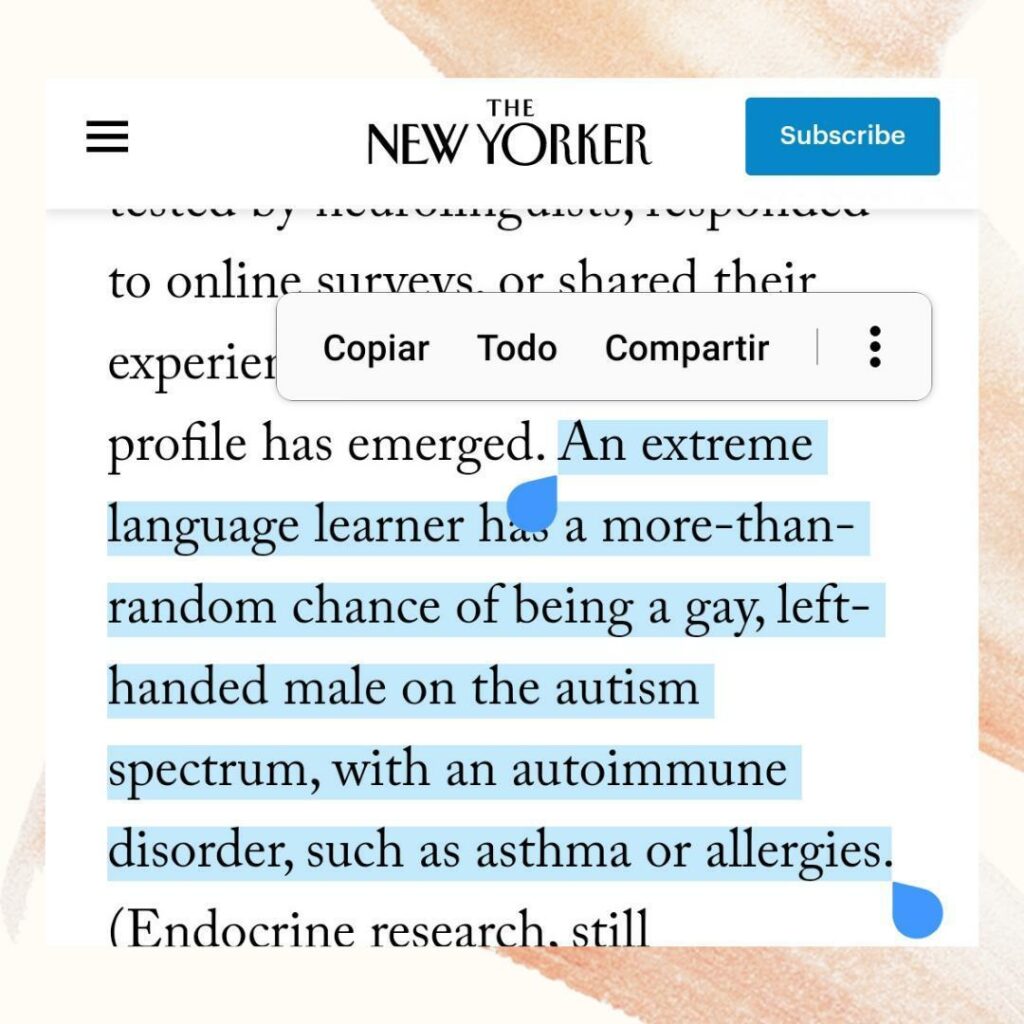

Are polyglots really more likely to be gay men?

That’s what this NY Magazine article suggests, as well as a follow-up survey by Alex Arguelles.

But both surveys were extremely small and limited to an elite group of language learners. They hand-selected candidates out and assumed there was something “special” or “unique” about those groups. Both were more anecdotal evidence than true studies.

So who do these surveys serve?

In March 2021, Relearn A Language launched a community survey for and by language learners

Our goals were:

To determine who within the population of online language learners considers themselves a “polyglot” or “hyper-polyglot”.

To fill in the gaps left behind by the laboratory surveys by reframing questions of gender and sexuality to reflect what is currently known about those identities. The goal was to give a more complete picture of the gender and sexuality identities within the entire community.

To ask additional questions about the motivations and experiences of online language learners–a distinct break from the neuroscientific outlook of previous researchers. Their goal was to find out what makes online language learners biologically or neurologically special, but we want to focus on unique social experiences learners may have had.

To organize groups within the language learning community not by the number of languages mastered (as Fedorenko and Arguelles did), but by some other identity or motivation. The goal was not only to potentially discover a unique pattern within language learners, but to possibly discover which demographics are most underserved by current market offerings.

Above all, the study would center the agency of individual learners in the community by creating an easily accessible survey for learners of every level; focusing on their motivation and experiences; and independently publishing the data and key findings for free.

After receiving 2,600 responses (well over our goal of 2,500) we closed the survey in May and began analyzing the data.

We also promised we’d release it all once we finished the process.

And as promised.... we have started to release our initial findings!

But before you start reading, you need to know that everything published here–right now–is just the tip of the iceberg.

By late summer 2021 we will have several times as many analyzed questions, as well as a complete academic report about our participants, methods, and results.

Initial Findings (June 2021)

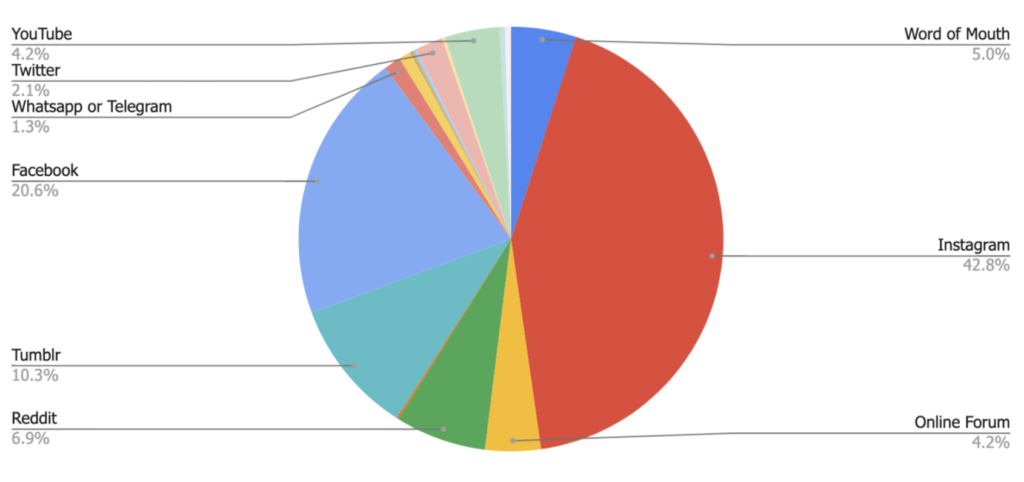

First of all: how did we find all of our participants?

We received over a hundred shares, including by podcasts and conferences, and it broke down like this:

The sources were important because it made sure that, unlike previous surveys, we did not pick participants from a limited pool of online learners.

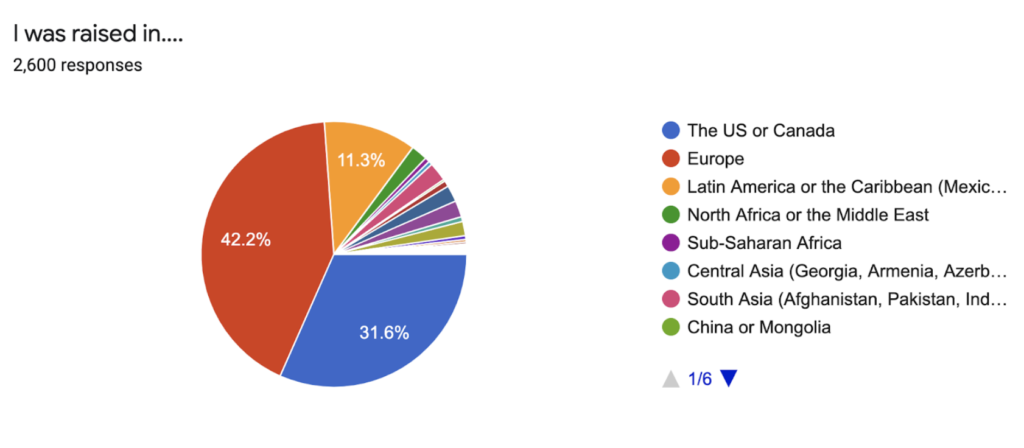

We also asked which global region participants were from.

This was not only to give us an idea who is in the online community of language learners, but to give us a cultural context.

As you’re going, keep this in mind.

Now let's dive into the first question we wanted to ask: are polyglots that large of a percentage of the online community?

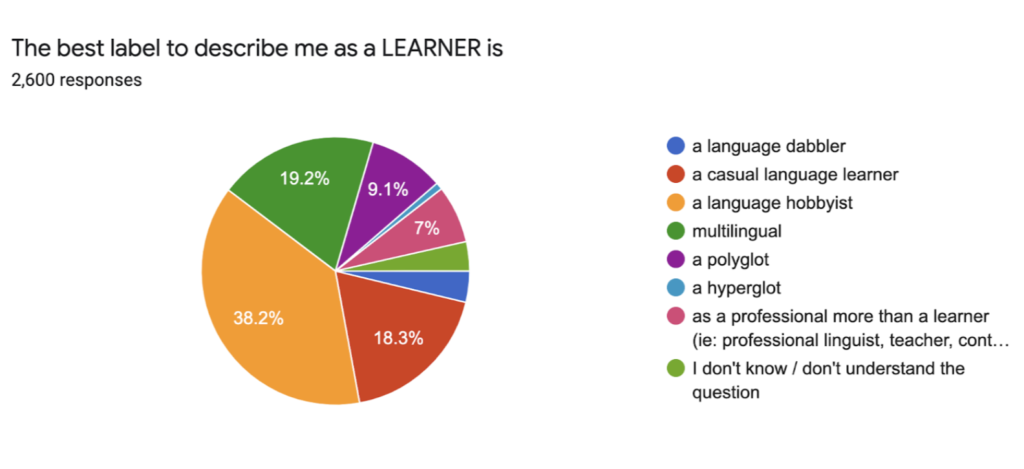

0.8% of respondents labeled themselves as “hyperglots” and 9.1% as “polyglots”.

(We’ll talk about how this interacts with gender soon.)

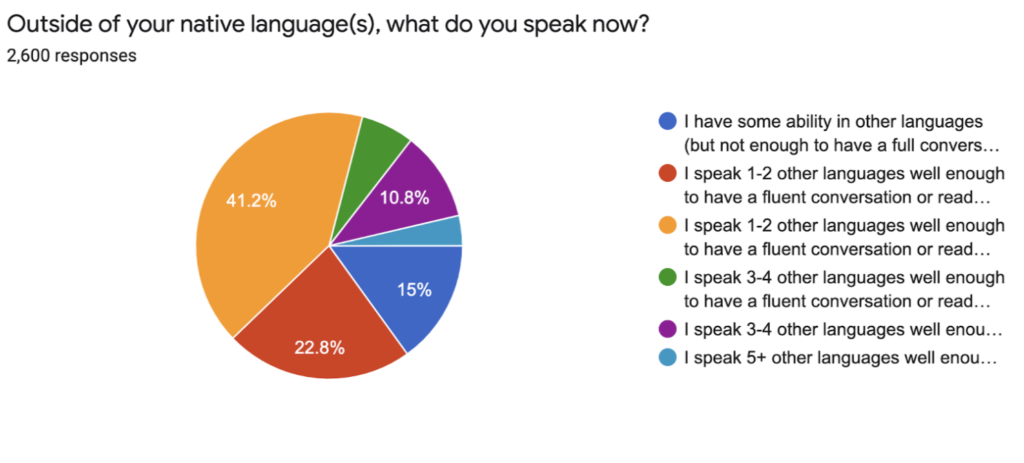

We can also see that learners who reported to speak 5+ languages (including their native language or languages) only 3.7% of total learners–meaning almost no language learners fall into the categories of “polyglot” or “hyper-polyglot” assigned by previous rearchers.

But how do language learners use these labels?

How many languages makes someone a polyglot? How many languages makes a hyperglot?

We can see that there isn’t a perfect definition from just glancing at the above two charts. But let’s dive deeper.

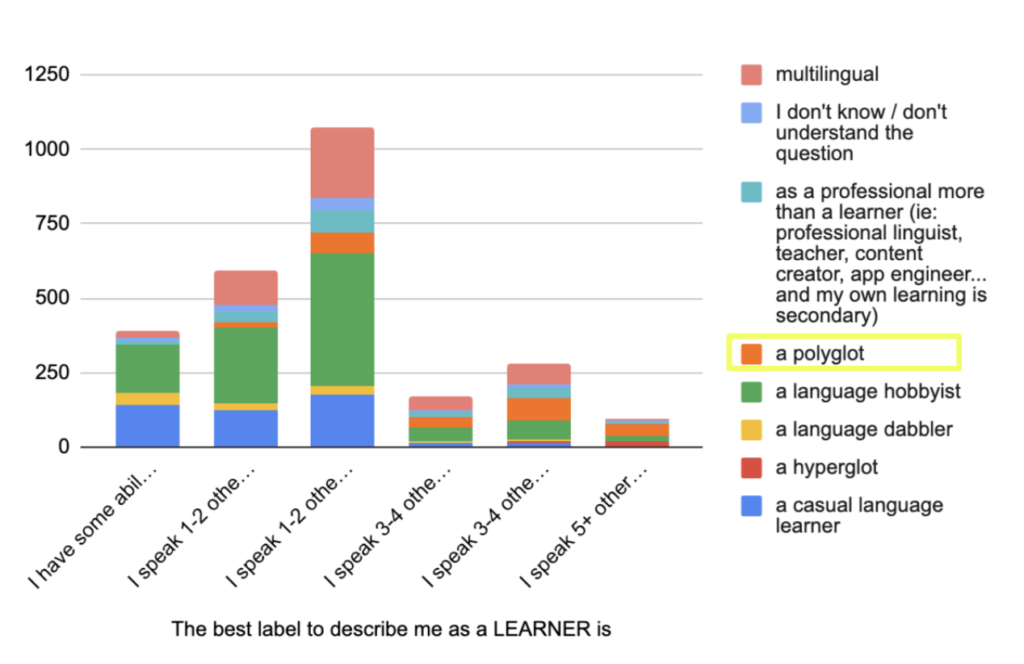

Here, we find that previous researchers’ use of the word “polyglot” does not fully align with how language learners themselves use the word “polyglot”.

- 4 people who labeled themselves polyglots also reported that they had “I have some ability in other languages (but not enough to have a full conversation with a native speaker stranger)”.

- Perhaps more surprisingly, another 84 people who spoke 1-2 “additional languages” (with or without abilities in others) labeling themselves as polyglots (around 35% of all people who labeled themselves as polyglots.)

- Only 17.3% of people who labeled themselves as a polyglot reported speaking 5+ languages, which is closer in line with the previous researcher’s definition of the word.

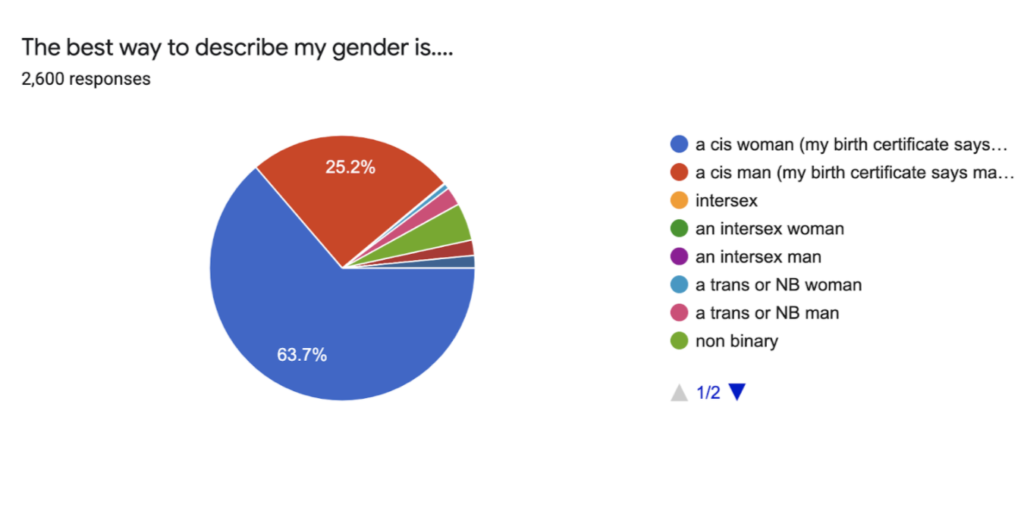

Now: are language leaners really more likely to be gay men?

Unlike previous surveys, we didn’t ask if someone was or “male or female”.

Why?

- Legally, citizens of Argentina, Australia, Denmark, the Netherlands, Germany, Malta, New Zealand, Pakistan, India, and Nepal have the right to a third gender option on federal documents, including passports.

- Central to linguistics and language learning, various indigenous people throughout North America recognize additional genders such as two-spirited and muxe–who, in some cases, may be important speakers of minoritized or endangered languages worthy of protection.

- Medically, it’s unknown how many humans have genitalia or secondary sex characteristics that are neither male nor female–but it’s estimated that at least 1 in 100.

(And those people are in the online community!)

I’m not sure about you, but when I saw this my jaw fell on the floor.

So why did the other surveys suggest that language learning was dominated by men?

(We’ll investigate that later.

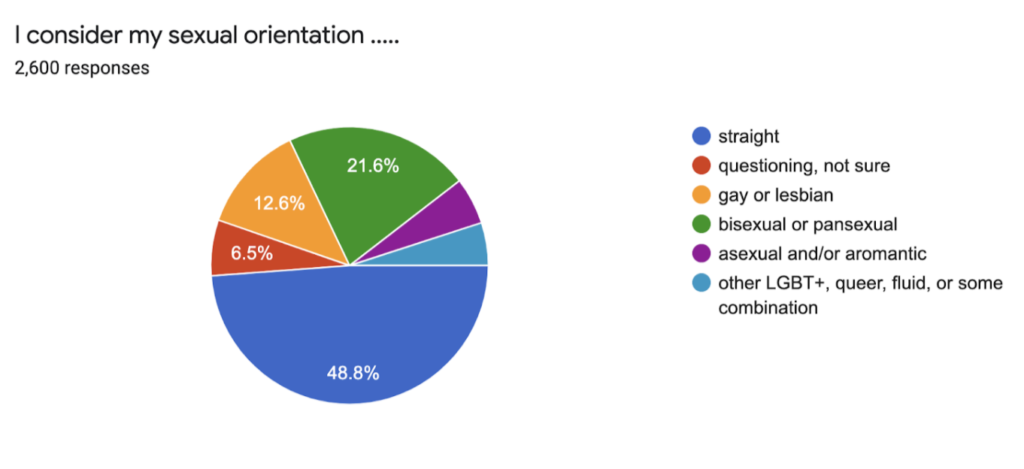

But we also needed to ask about sexuality.

The thing is, we didn’t ask if someone was “homosexual” or not.

There’s so much more to sexual identity than that!

So maybe we’re not exactly likely to be “gay men”…. but language learners certainly don’t seem to be straight men.

In future releases of key findings, we’ll try to find some reasons for why this might be (and why these results look so different than those in previous studies.)

Those were only a few of our findings concerning how we as learners experience life in the online world of language learning.

Now, let’s dive into how our first subsection of learners form a part of the community.

Key Findings on LGBTQAI+ Experiences

After looking at the initial findings posted above, we were left with two big questions:

- If men are in the minority, why did they come out as the majority of “polyglots” in the other surveys?

- If there are so many people who fall into categories of neither “man” nor “woman”, neither “straight” nor “homosexual”, then why hasn’t anyone else brought attention to that before?

So we decided to test three hypothesis:

- That men are more likely to label themselves as polyglots or hyperglots.

- That LGBTQAI+ people feel less represented by the language learning resources currently on the market.

- That LGBTQAI+ people feel less a part of the online language learning community.

Let’s see the results.

A Quick Note on Labels

From now on, you’re going to see three labels that we’ll use to refer to different groups of learners.

- Trans+ is the marker we will use to denote all survey participants who are not cisgender.

- LGB+ is the marker we will use to denote all survey participants who are not heterosexual.

- LGBTQAI+ is the marker we will use to denote all survey participants who are not cisgender and heterosexual.

The reasons we believed these markers were important in the context of this survey is because (1) with the changing and updating of words, there has never been any single agreed-upon definition for umbrella terms within the community, and (2) markers like “not cis” or “not straight / hetro” would center straightness and gender binary when, in fact, we are discussing very different social experiences.

(Readers are also urged to remember that a transgender person may rightfully identify as straight, just as a lesbian or gay person may identify as cis. Both are still welcome parts of the LGBTQAI+ community, just as many participants who fall into any of these three categories may lead heteronormative lives.)

Men+ and Women+ are how we will refer to groups of cisgender, intersex, trans, and/or nonbinary men and women. We will refer to learners who were assigned one gender at birth and maintain that gender as an adult as “cisgender men” and “cisgender women”. We will avoid the stand-alone “men” and “women” when referring to our own data to avoid confusion.

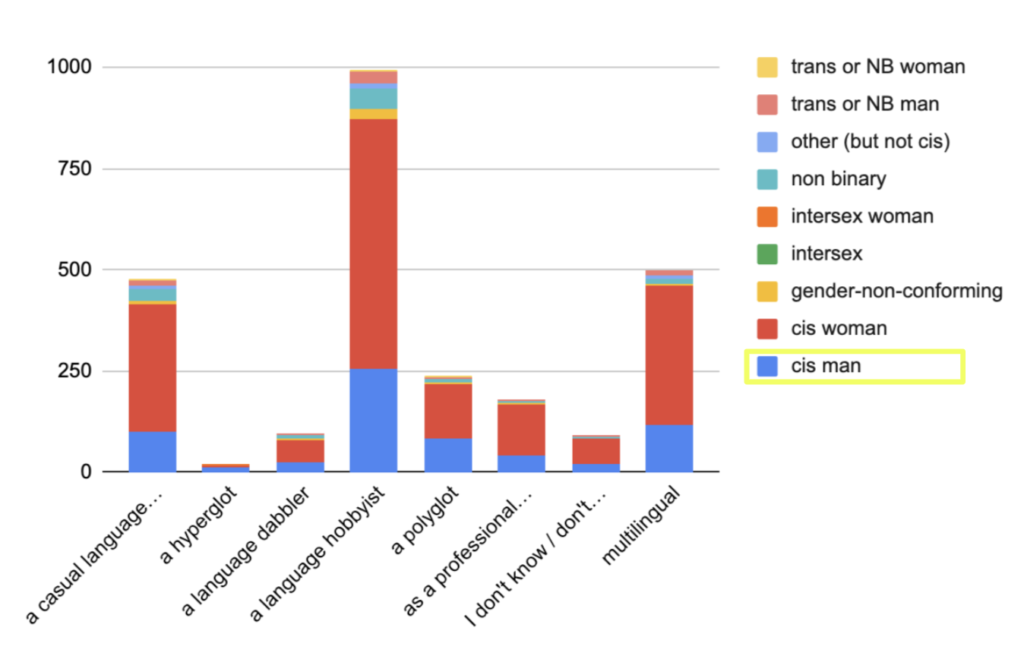

How do different genders label themselves as learners?

In the following graph, we will take a closer look at the labels language learners are using for themselves–this time, by gender.

Since cismen have been the supposed majority, we’ll pay special attention to them.

Note that cis men’s distribution in all categories was relatively even with their overall presence in the community, with the exception of the “hyperglot” category.

Out of 22 respondents who identified as hyperglots, 13% identified as men–consistent with previous researchers’ findings that polyglots are slightly more likely to be men.

But is that self-selection of a preferred identity label, or a reflection of the learners’ actual skills?

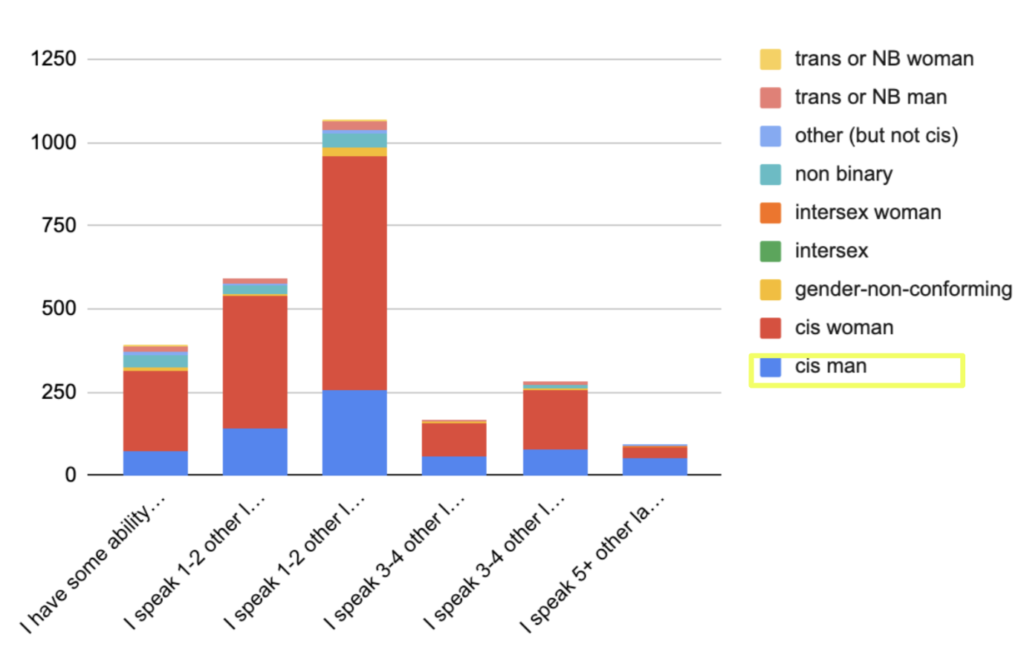

We again see men who claim they speak “5+ other languages well enough to have a fluent conversation or read a novel” make up a larger percentage of that category than any other. (51 out of 95 participants.)

This is again consistent with previous researchers’ findings, although all categories are self-reporting and are not indicative of any language user’s actual measured skill in a standardized language.

Examining these two charts, we can conclude that cisgender men do make up a larger proportion of the subgroup known as “hyper-polyglots”.

But why is that?

We can try to find out in the following two questions.

How often do LGBTQAI+ people see themselves represented in language learning resources?

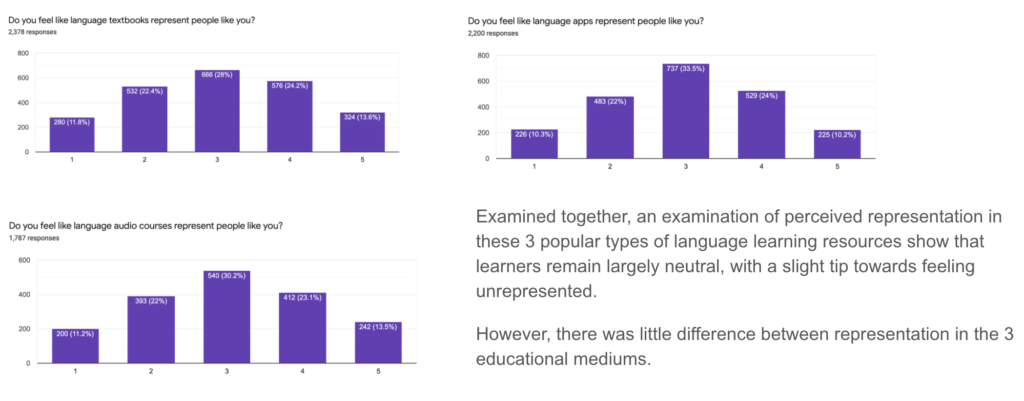

First, let’s establish how often the language learning community as a whole sees itself represented in various language learning materials.

We asked participants to rank how often they felt represented in (1) apps (2) textbooks and (3) audio courses.

Participants were asked to rate each resource

from 1 (“[Resource] always represents people like me”)

to 5 (“[Resource] never represents people like me”).

Participants were allowed to skip a question if they had never used a resource like that.

As you can see, language learners fell neutrally across the spectrum.

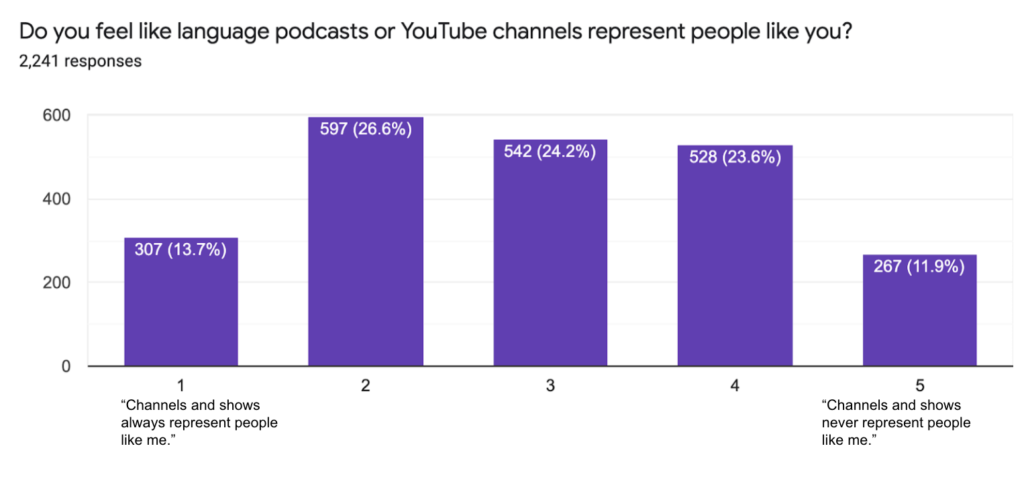

But what happened when we asked about podcast and YouTube representation?

Ok… now things are starting to get interesting.

However, because this post is only a small taste of what’s to come, we’re going to examine only the representation in apps next.

We’ll post our analysis of other mediums within the next two months as part of the larger release.

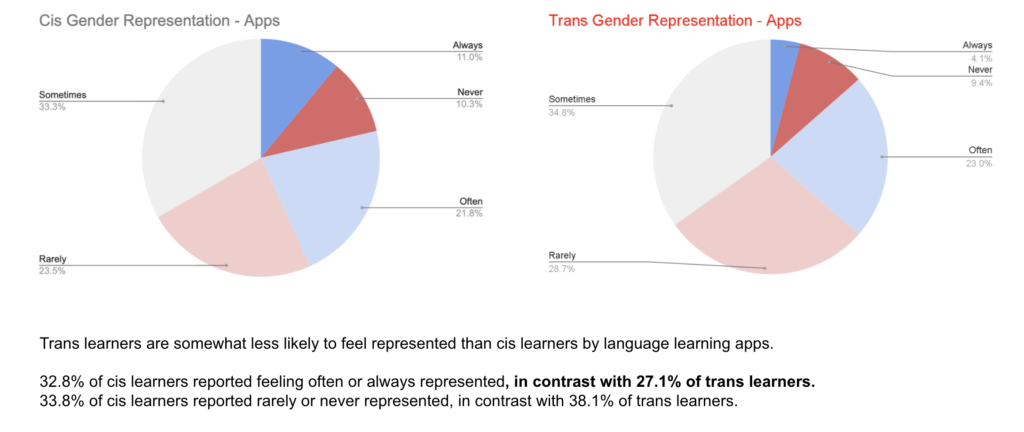

Trans+ learners are somewhat less likely than cis learners to feel regularly represented in language learning apps.

It makes sense on the surface, right?

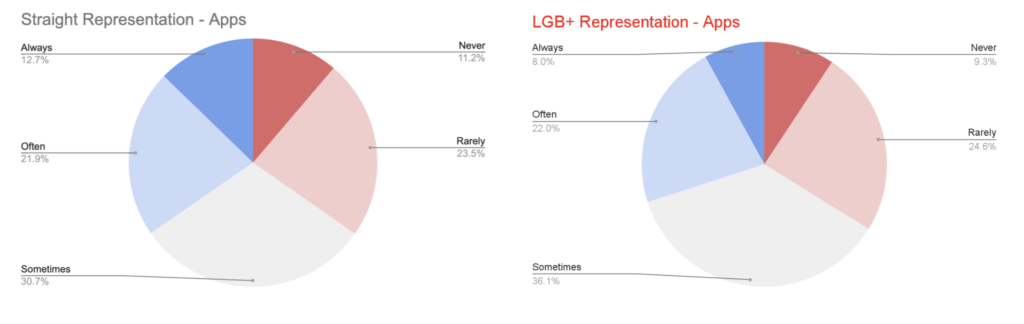

So the same thing should hold true for sexual orientation–that LGB+ learners would feel less represented than straight learners?

But LGB+ learners reported feeling never or rarely represented 33.9% of the time.

And straight learners reported that they feel never or rarely represented 34.7% of the time.

It’s worth noting, however, 30.0% of LGB+ learners stated they are often or always represented (vs 34.6% of straight learners).

And there are other dynamics at play–since this is an international survey, language learners in regions where LGBTQAI+ attraction or behavior is criminalized may be less likely to be out of the closet, but also less likely to see themselves regularly represented in media.

But the short of it is: we don’t know why this might be.

So let’s see if we can find anything that might shed light on the question in our final segment of this release.

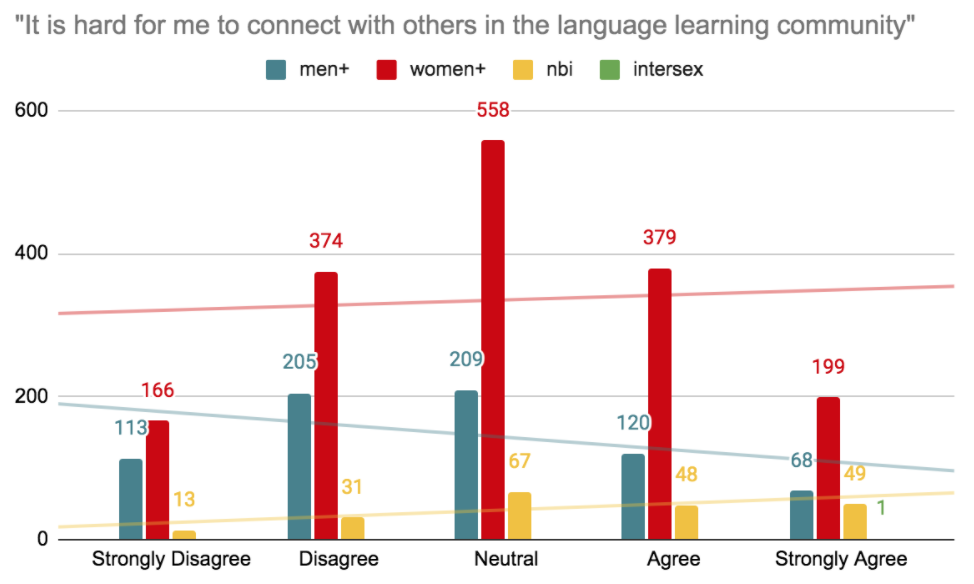

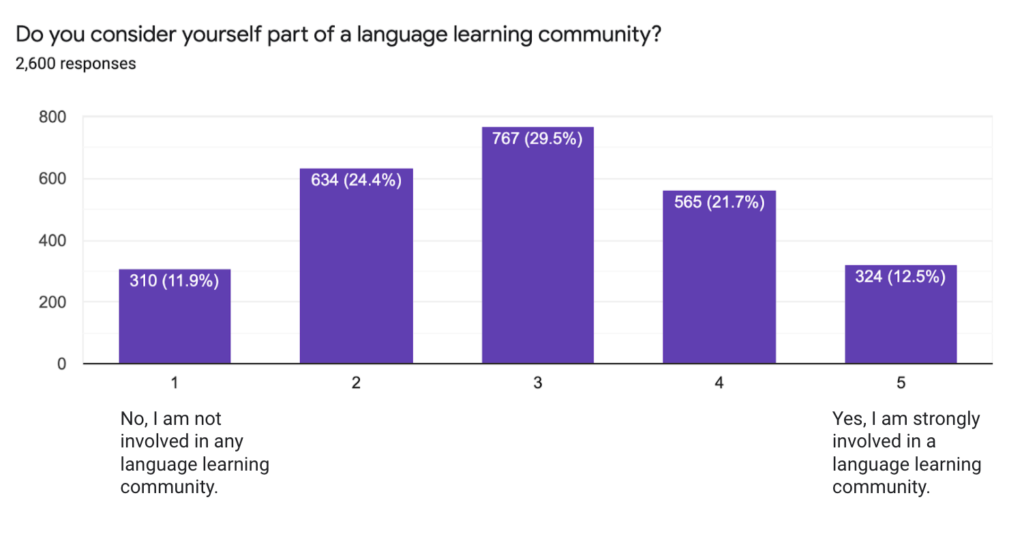

Do LGBTQAI+ learners see themselves as part of the online language learning community?

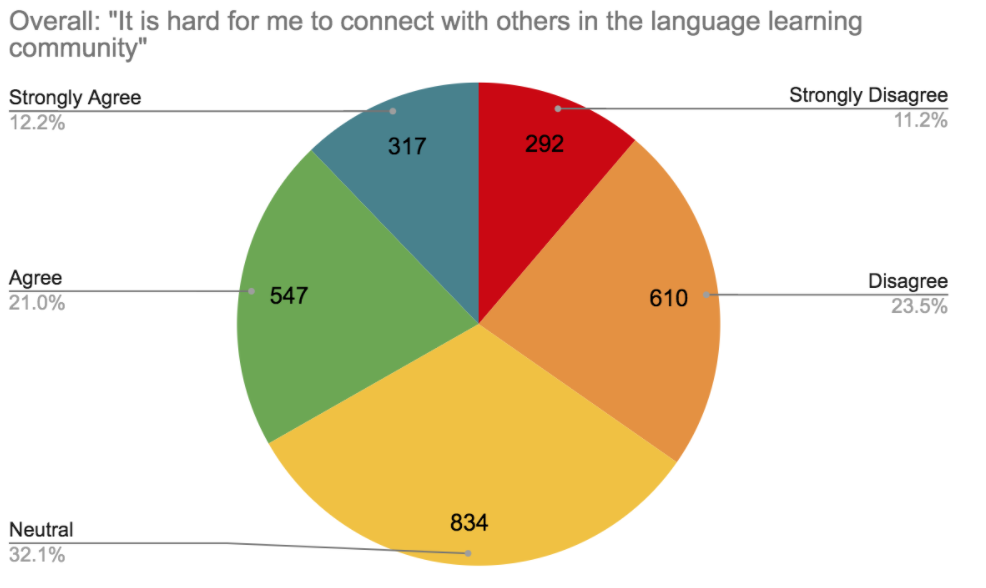

First, of course, we need to see how all language learners as a group responded.

Considering participants found the survey through community channels, it might be somewhat surprising to see that online language learners tip slightly towards not feeling like they’re part of the community.

Could that be because of how they’re represented? We’ll take a look at that in reports of key findings.

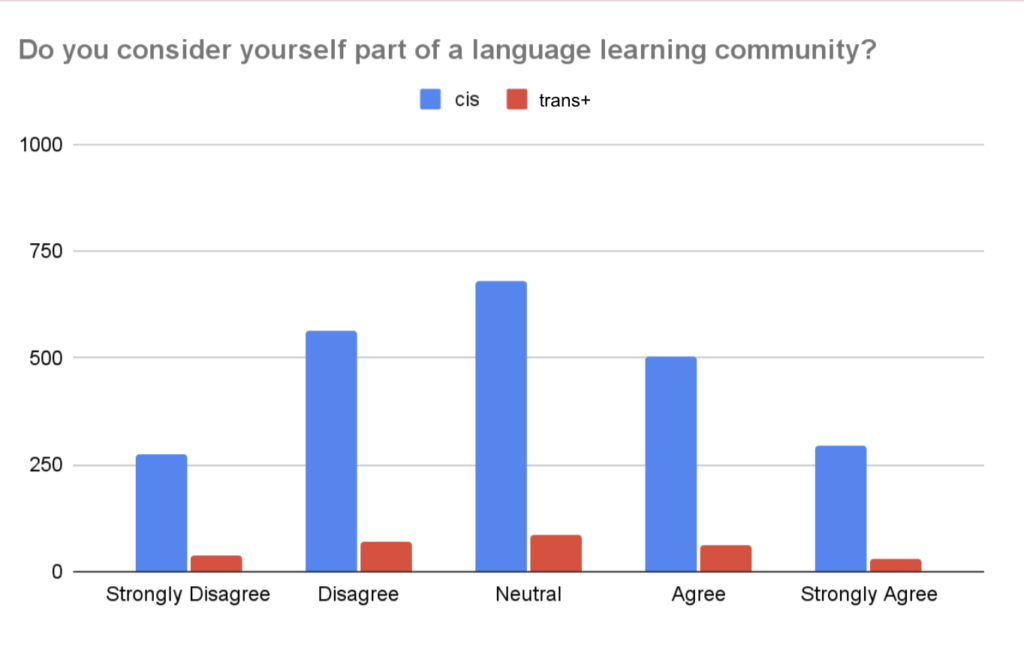

Both cis and trans+ participants reported extremely similar feelings of belonging within the community: largely neutral but lightly tipping towards disagreeing.

- 24.3% of cis participants disagreed

- 24.7% of trans participants disagreed

- 11.8% of cis participants strongly disagreed

- 12.9% of trans participants strongly disagreed

Trans+ language learners disagree only slightly more than cis counterparts that they are part of a language learning community.

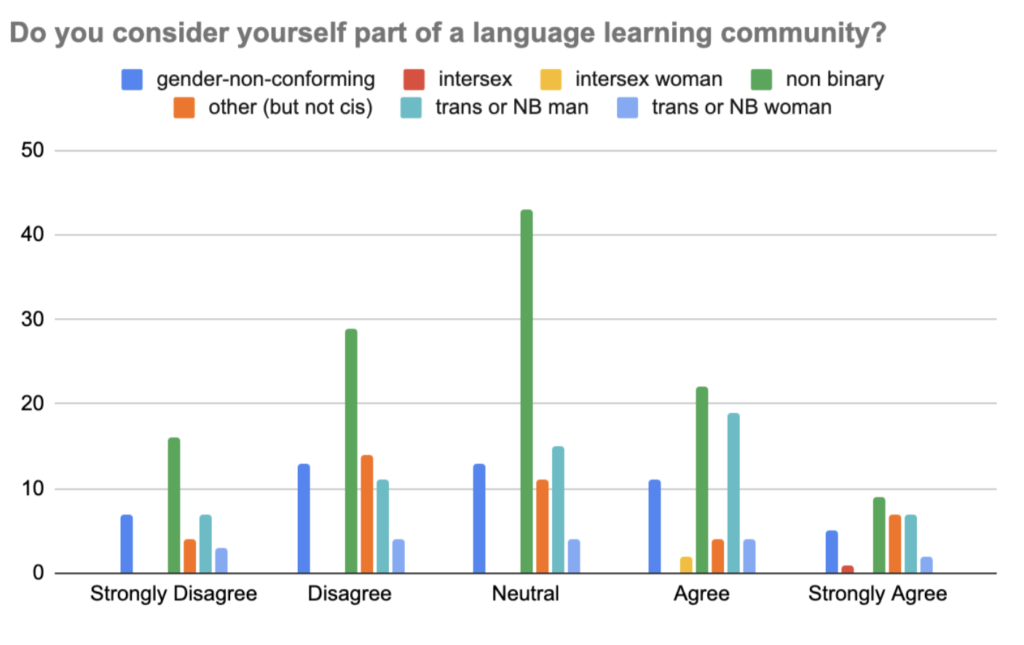

But what about identities within the trans+ umbrella?

Here we can see a more stark difference.

“Trans or nonbinary men” were more likely to see themselves as part of the community than almost any other trans+ identity. (32.2% agreed that they are part of a language learning community.) The few intersex language learners who responded to the survey also felt more positively, although the sample size was small.

Participants who did not select a specific trans+ identity (but did not identify as cis) were by far the most likely to disagree (35.0% disagreed).

Now let’s see if we can find any patterns when looking at sexual orientations.

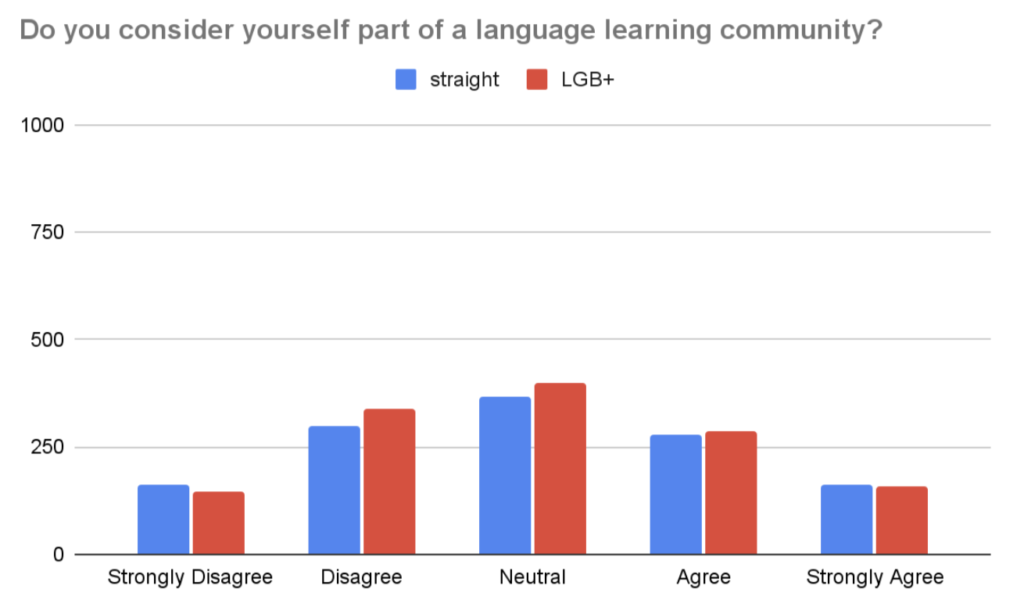

Curiously, there is no strong difference between how straight and LGB+ sexualities correlate with a sense of belonging.

- 36.3% of straight participants disagreed or strongly disagreed, although they made up a larger proportion of “strongly disagree”.

- 36.2% of LGB+ participants disagreed or strongly disagreed, although they made up a larger proportion of “disagree”.

- 34.8% of straight participants agreed or strongly agreed, although they made up a larger percentage of “strongly agreed”.

- 33.7% of LGB+ participants agreed or strongly agreed, although they made up a larger percentage of “ agreed”.

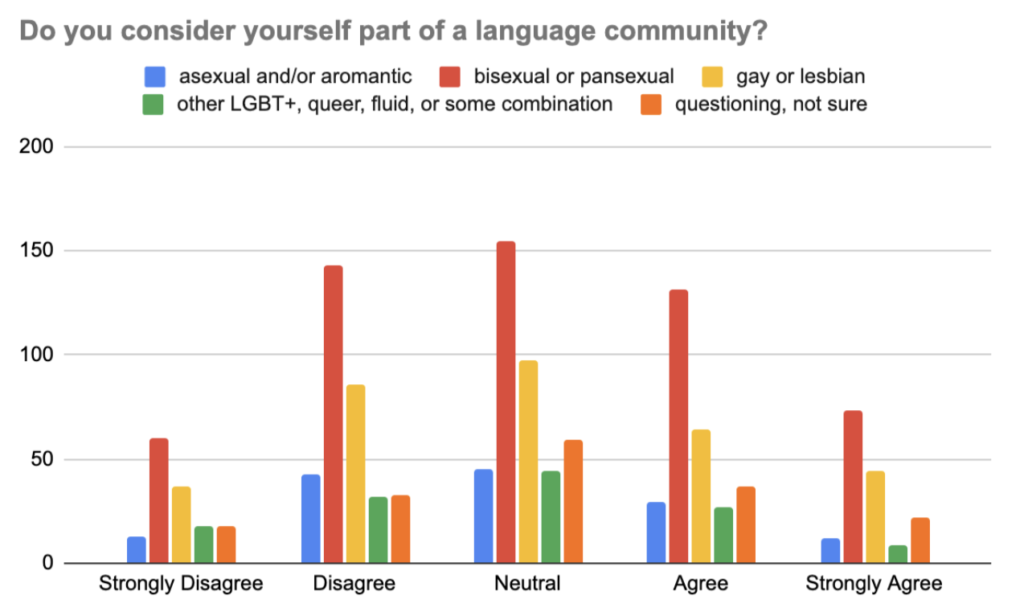

Seen together, a learner’s individual identity seems to have more impact on how they see themselves in the community in contrast with whether or not they identify as straight.

- Asexual/aromantic people were the most likely to disagree or strongly disagree (39.4%) that they were part of the community.

- Those who are questioning their sexuality are the least likely to disagree or strongly disagree (only 30.2%–making them the only group to disagree less than straight counterparts).

- Bisexual or pansexual were the most likely to agree or strongly agree that they were part of the community, at 36.3%. (This is at a higher rate of inclusion than this straight counterparts.)

- “Other… (but not straight) were the least likely of every group to agree or strongly agree that they were part of the community, at only 27%.

So do we have a lot of answers?

Maybe, maybe not.

But the good news is we have a ton of additional questions we can analyze!

Key Findings on Community (November 2021)

Our next phase of data analysis focused on interactions within language learning spaces.

After finding large differences in how different gender groups labeled themselves as learners (but fewer differences in how they saw themselves represented in learning materials) we decided to continue exploring along the lines of gender in this next phase of analysis.

The questions we wanted to answer were:

- What kind of reported experiences do language learners have with:

- other online learners?

- native speakers of their target language?

- tutors and teachers?

- general populations?

- Regardless of the outcome, do they anticipate these experiences to be positive or negative before the experience takes place?

- Does the gender of a learner impact their anticipated or real experiences within the community?

We also wanted to analyze questions about their perceptions of interactions within the community:

- Do they perceive different genders and sexualities as treated equally within the community?

- Do they themselves have any bias when interacting with various genders?

1. What kind of reported experiences do language learners have with other online learners?

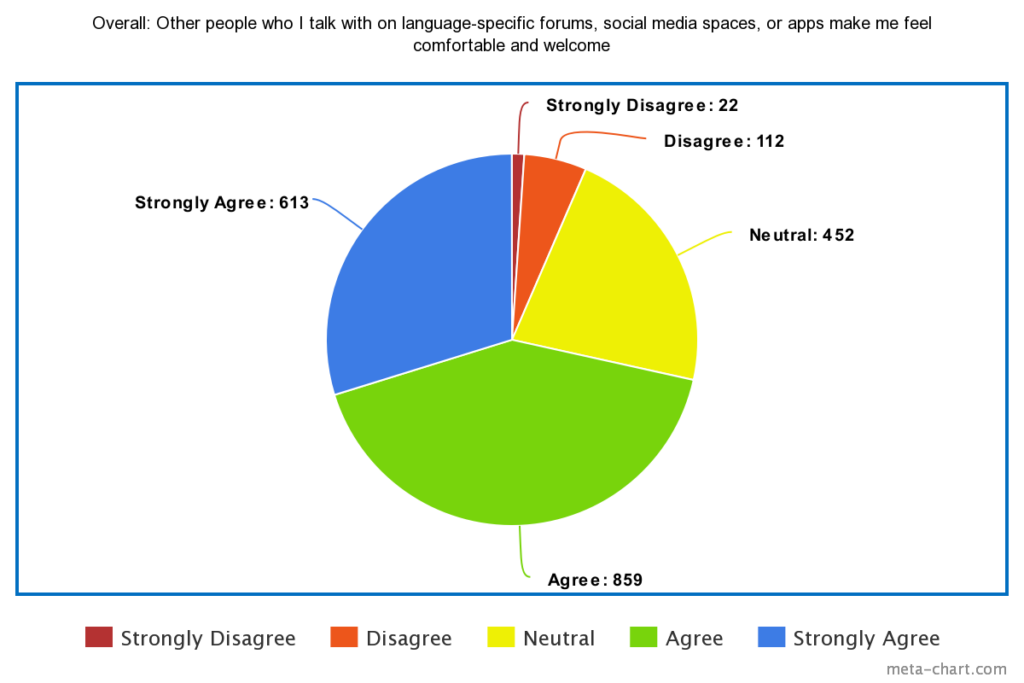

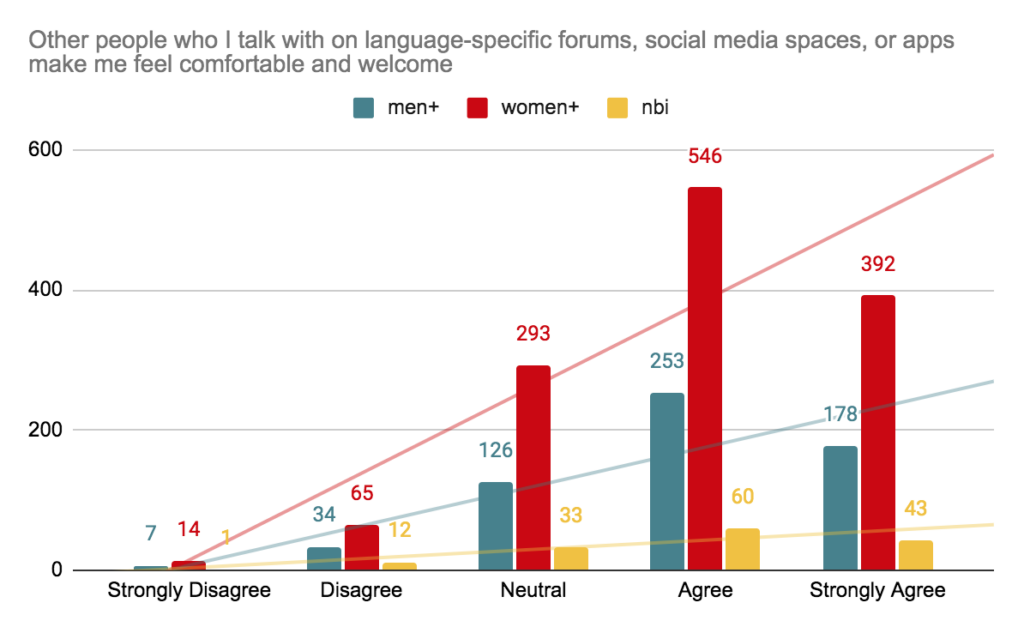

Language learners overwhelmingly reported positive experiences other people in online community spaces.

Out of those who have interacted in community spaces, 71.46% reported to agree or strongly agree that their real interactions made them feel “safe and welcome”.

This is compared to 6.39% who reported to disagree or strongly disagree.

We could draw a few tentative assumptions from this data.

First, it’s possible that despite positive external social experiences, the internal experiences of language learners trend more negatively in social situations. The data does not explain why internal experiences may not match interpersonal experiences.

Second, it’s possible that positive social experiences remain shallow, indicating a market need for more tight-knit or long-term community in the online spaces.

The question as to why woman+ and nonbinary learners feel that it’s hard to connect with other learners should also be additionally explored.

2. What kind of reported experiences do language learners have with native speakers of their target language?

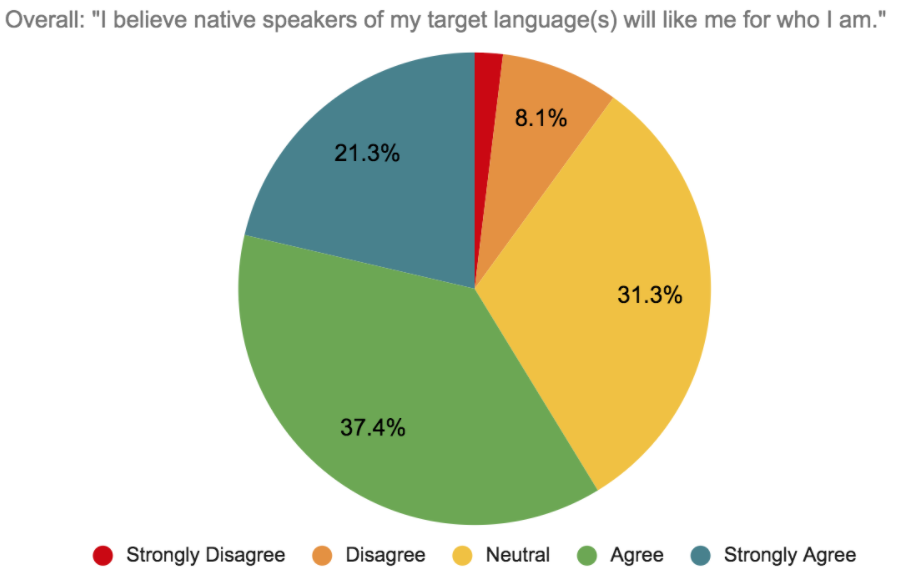

When asked to report on their own beliefs about the perceptions of others, we once again saw that the majority of learners agreed or strongly agreed that native speakers of their target language would like them for “who [they are]”.

We could categorize this as a positive perception of an external, interpersonal experience.

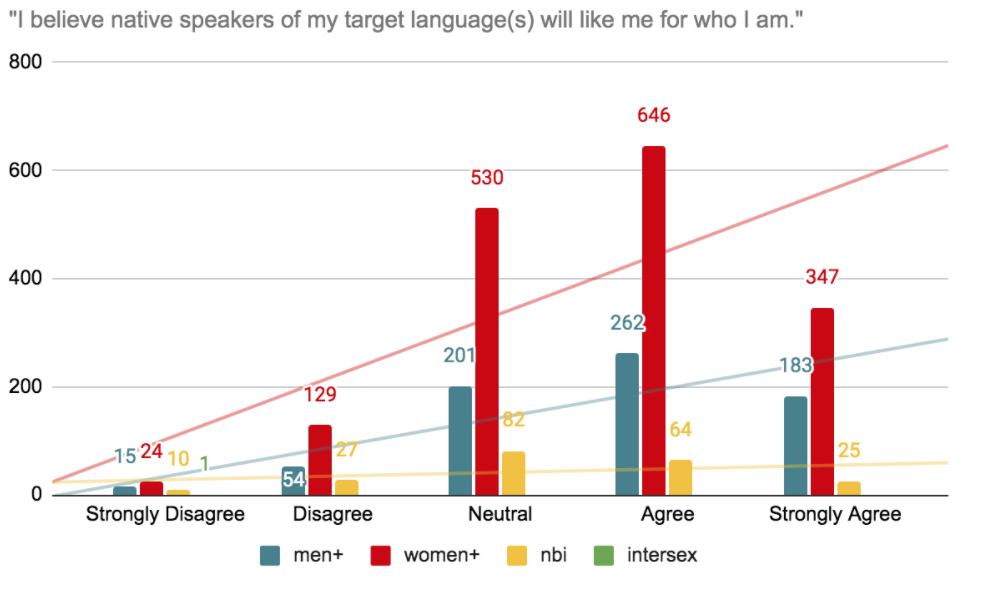

For women+ and men+ this trend was consistent with the group as a whole, with nonbinary learners leaning slightly more neutrally than the two binary genders.

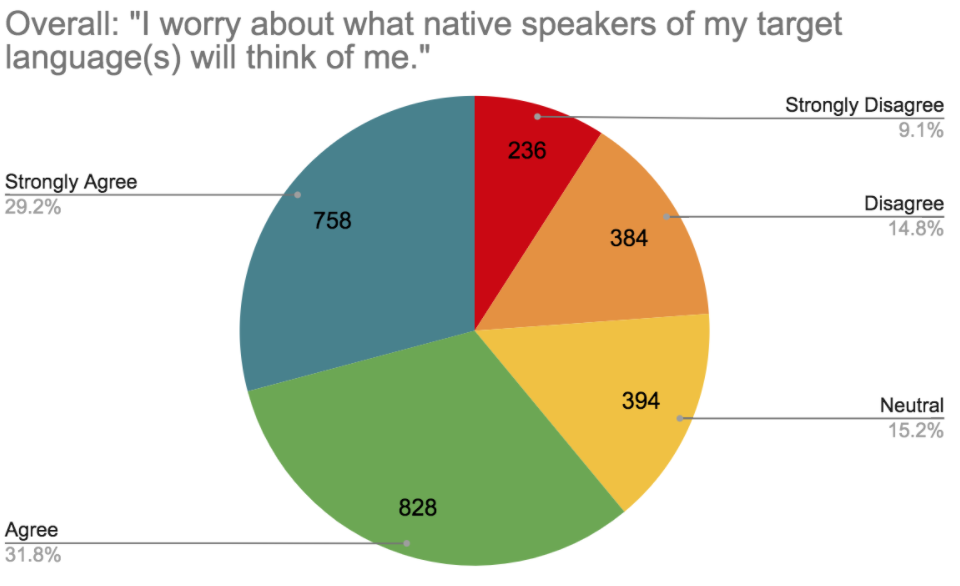

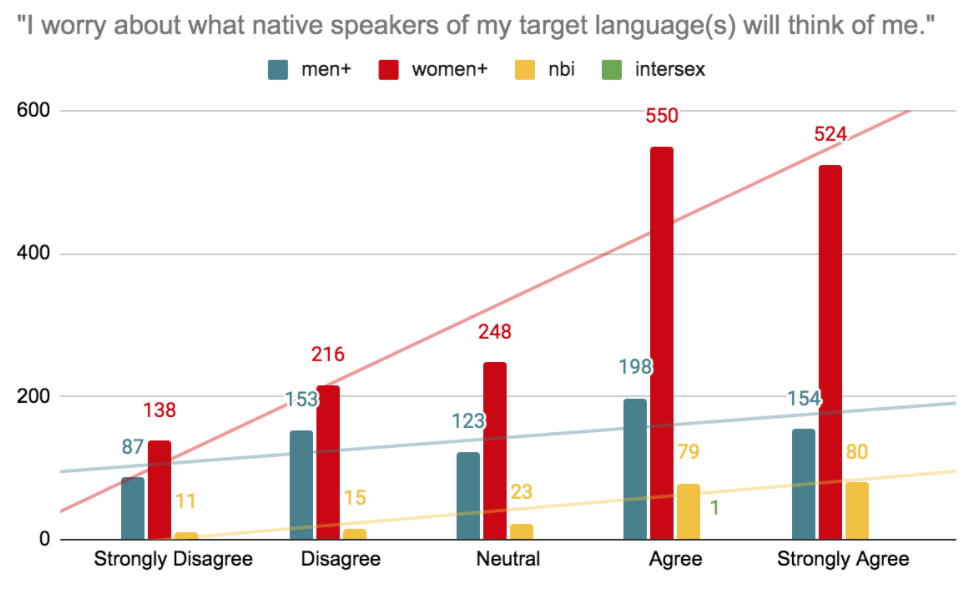

That said, when asked if they were worried about what native speakers thought of them, the majority answered that yes, they agreed or strongly agreed that they worried.

Women+ and nonbinary learners reported exceptionally high rates of “worry”.

Men+, interestingly, trended somewhat more neutrally but were actually more likely to disagree or agree than to report that they are neutral on worry.

Once again we can see a discrepancy between potential lived experiences and internal experiences surrounding social situations. Additional questions around why language learners are having and perceiving social interactions in two very different ways should be asked in the future.

However, the internal emotional experiences of women+ and nonbinary people should be highlighted here, especially noted by tutors, language education companies, and language exchange participants.

3. What kind of reported experiences do language learners have with tutors and teachers?

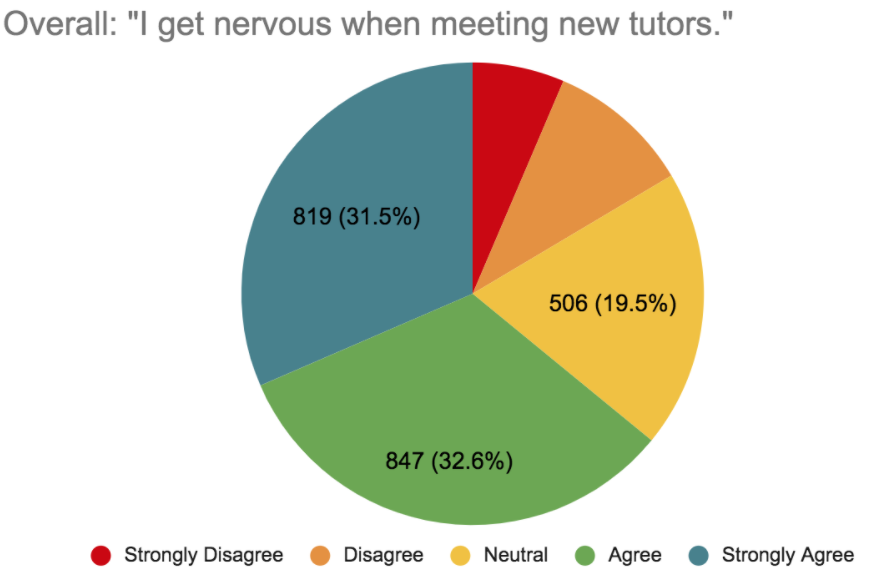

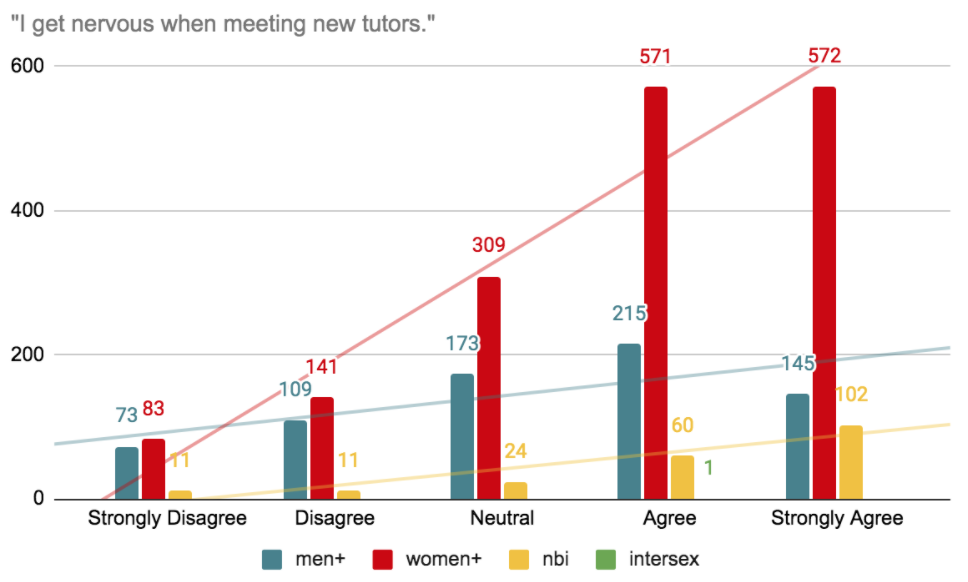

Finally, we asked a negative question about tutors. The overwhelming majority agreed that they “get nervous when meeting new tutors”.

Although all genders trended in agreement with being “nervous”, men+ once again trended more lightly than other gender groups. 50.34% of men+ agreed or strongly agreed that they were nervous.

Out of 1,676 women+ learners, 68.19% agreed or strongly agreed that they were “nervous”.

Out of 209 nonbinay learners, 77.51% agreed or strongly agreed that they were nervous, with “strongly agreed” being almost half of all nonbinary learners.

It’s worth nothing here that in the past 2 questions, women+ and nonbinary students reported to be both more “worry” and “nervous” when interacting with tutors and native speakers.

Given our understanding of stress and anxiety on the brain’s ability to learn and remember, future researchers should consider asking about students’ stress levels during language learning sessions, and if there differences by gender.

These negative internal experiences also may indirectly explain part of why men+ are reporting their own language levels as higher than other gender groups.

4. What kind of reported experiences do language learners have with general populations?

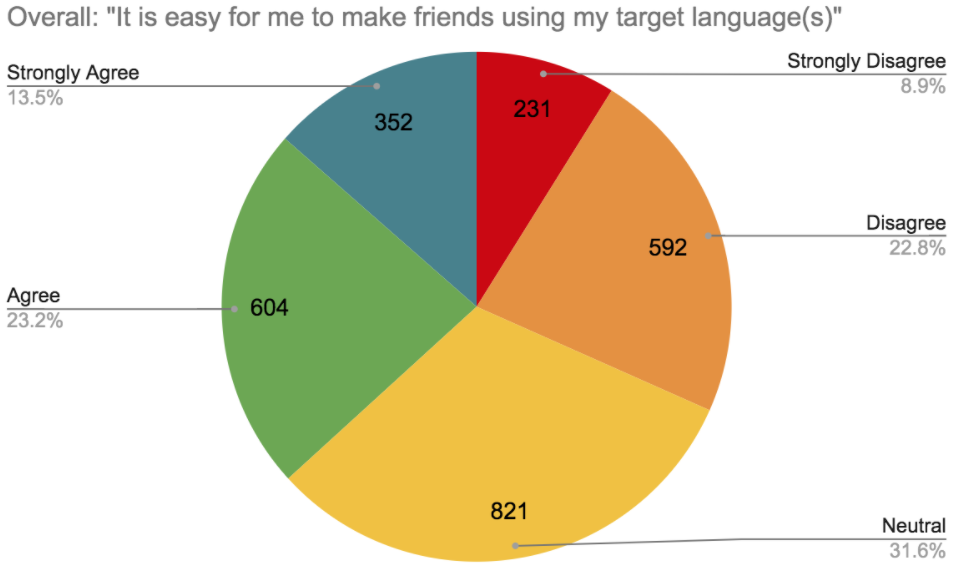

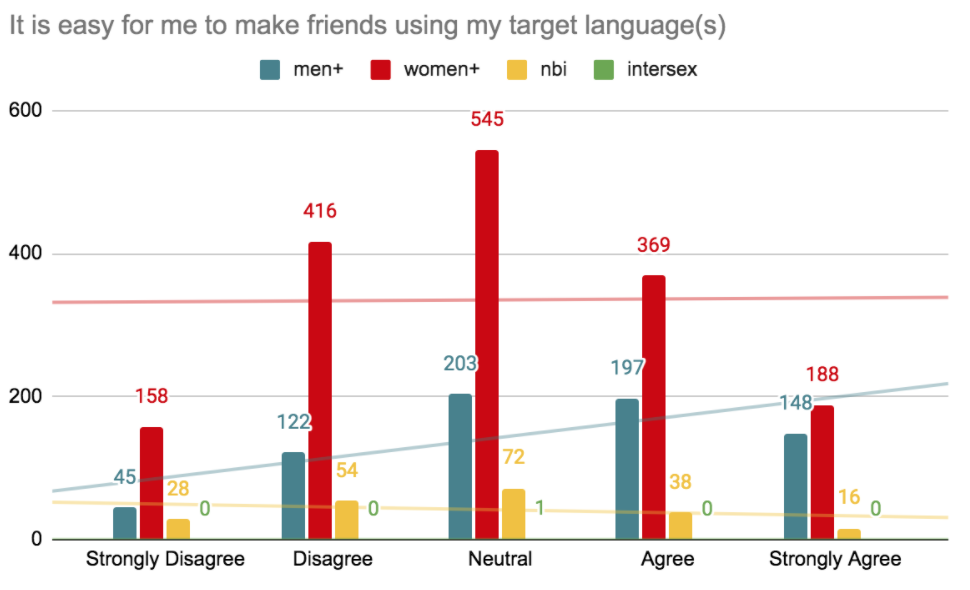

When asked about the ease of making friends, the larger group was largely divided as to whether or not it was easy to make friends using a target language.

However, here we see that gender experiences vary the most widely out of any question so far.

Women+ are almost perfectly neutral on the question, with men+ tending to agree that it’s easy “to make friends” using a target language.

However, nonbinary learners are the one group that substantially trends negatively, with 39.42% saying they disagree or strongly disagree, and only 25.96% agreeing or strongly agreeing.

We once again see that the experiences of nonbinary language learners need to be highlighted.

As we saw earlier in this survey, 1 in every 10 online language learners do not fall into the categories of “man” or “women”. These learners are not a small, fringe group.

Their reported “worry” and “nervous” feelings at a higher rate may have real neurological consequences on their abilities to synthesize and remember new information. Their disagreeing that it is “easy to make friends” may findings may indicate larger and more systematic problems and/or opportunities within the online language learning space.

For the next section, we move on to questions about the perceptions learners have about gender equality within the online language learning space.

5. Do learners themselves perceive different genders and sexualities as treated equally within the community?

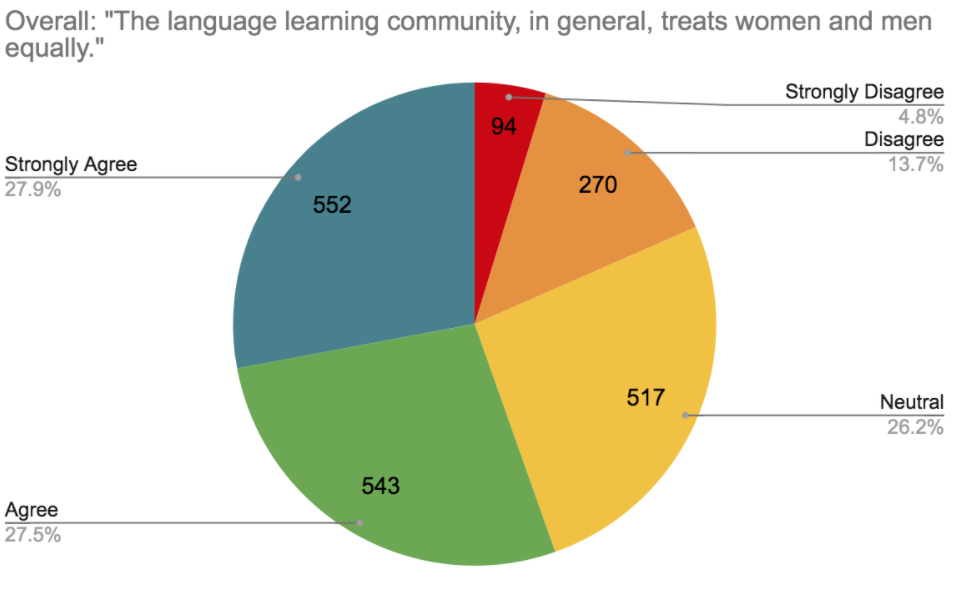

The larger group largely thought that “men and women” were treated equally.

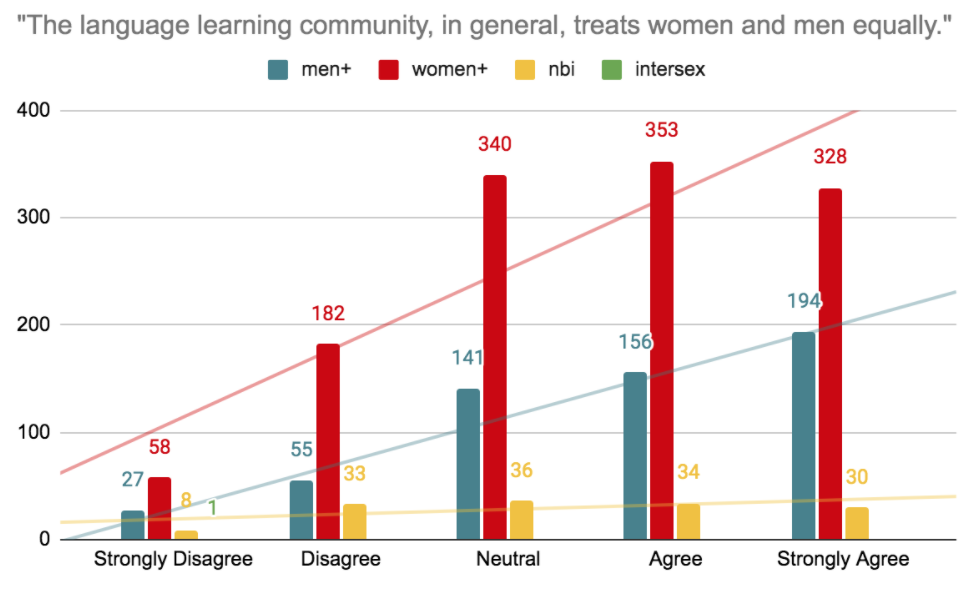

When broken down by gender however, perceptions of gender equality varied slightly.

14.31% of men+ learners disagreed that women and men were treated equally.

19.03% of women+ learners disagreed that women and men were treated equally.

29.07% of nonbinary learners disagreed that women and men were treated equally.

Nonbinary learners are the most critical of binary gender inequality of the group, being almost 2x as likely as men to disagree that there currently exists equal treatment.

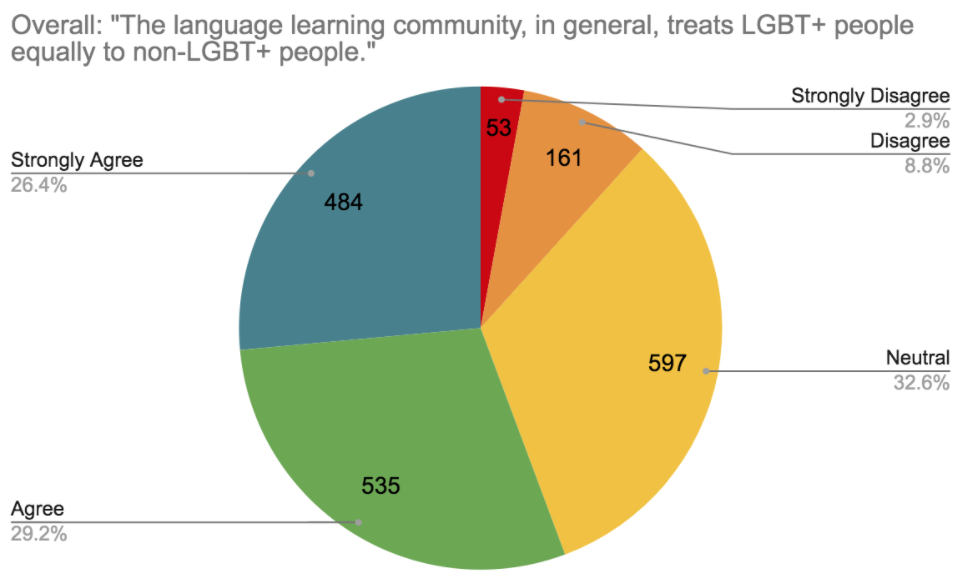

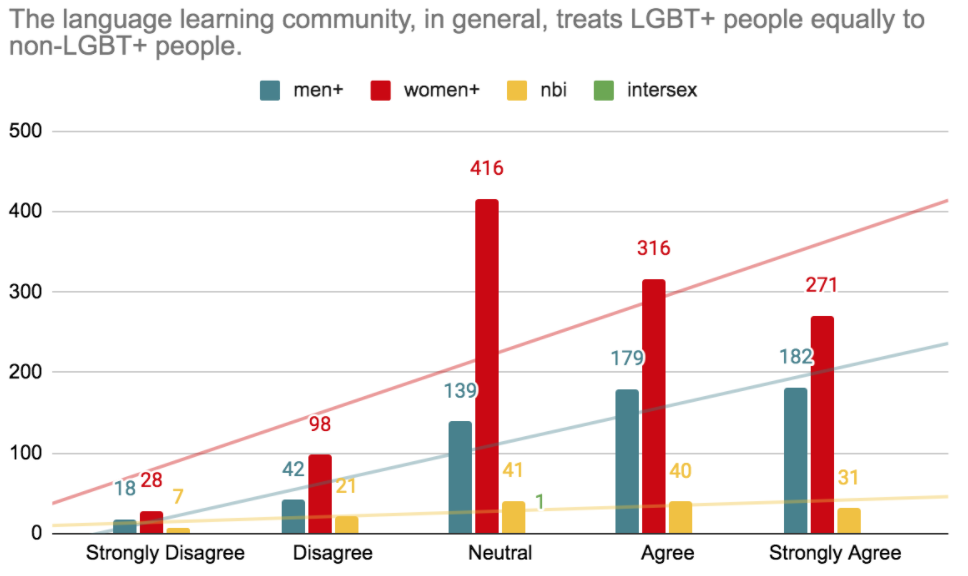

The perceived treatment of LGBT+ people vs the treatment of cishet people was slightly more neutral (32.6% reporting perceived lgbt+ neutrality vs 26.2% on binary gender neutrality).

However, the results are relatively close.

The perceived treatment of LGBT+ people trended similarly to the treatment of binary genders.

It’s important to note that questions about equality did NOT specify any preferential treatment towards one gender over others.

So, some learners who disagreed with statements of binary gender equality might think the community may think the language learning community treats women better than men, while others who disagreed with the same statement may think the community treats men better than women.

However, interestingly enough, it seems that LGBT+ equality with cisgender hetrosexual learners is less contentious within language learning spaces than the equality between men and women.

What does that mean for the learners’ own biases?

In this last batch of questions, we began to explore how learners reported their own interaction and preferences.

6. Do learners themselves have any bias when interacting with various genders?

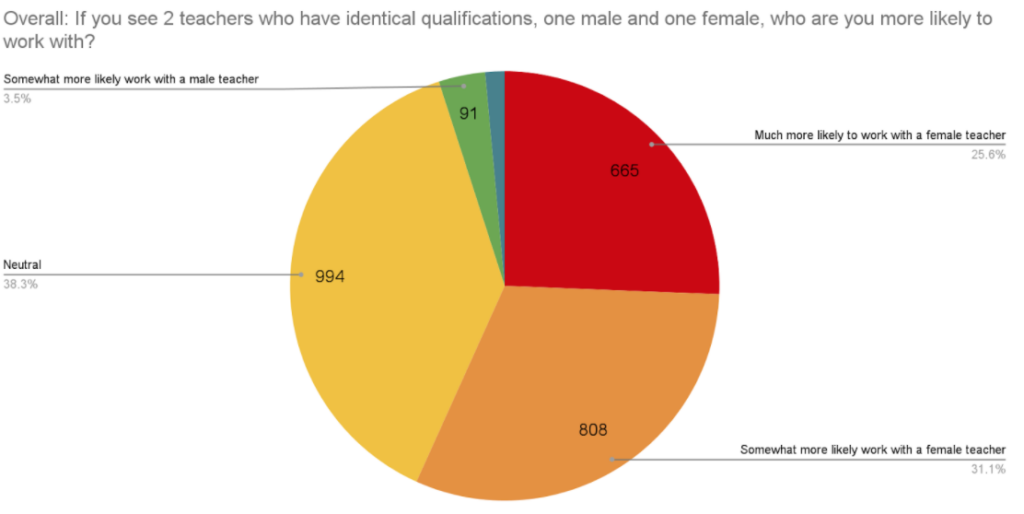

Overall, learners reported that they were overwhelmingly more likely to work with women than men.

This is especially interesting in the context of perceived gender equality or inequality in the last question.

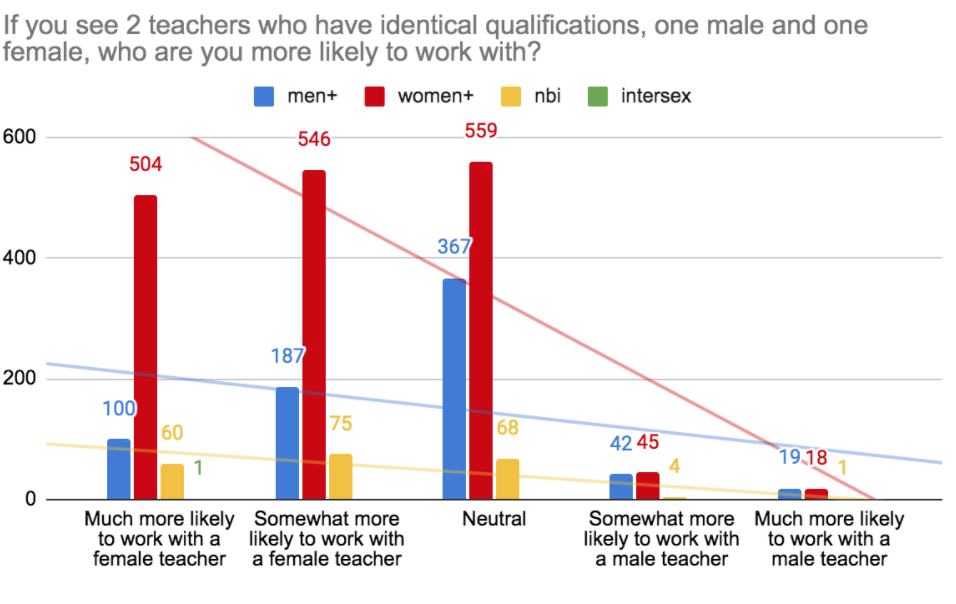

Broken down by gender group, this might be the most surprising discovery of all.

All genders were more likely to choose a “female teacher” over a “male teacher”, with almost no nonbinary learners preferring male teachers.

Women+ and nonbinary learners were extremely unlikely to work with men, with only 3.76% and 2.4% (respectively) saying they were more likely to work with a male teacher.

Men+ were also less likely to work with men (8.53%).

(As a quick note for this question and the next, it’s important to remember both women and men may be LGBTQAI+.)

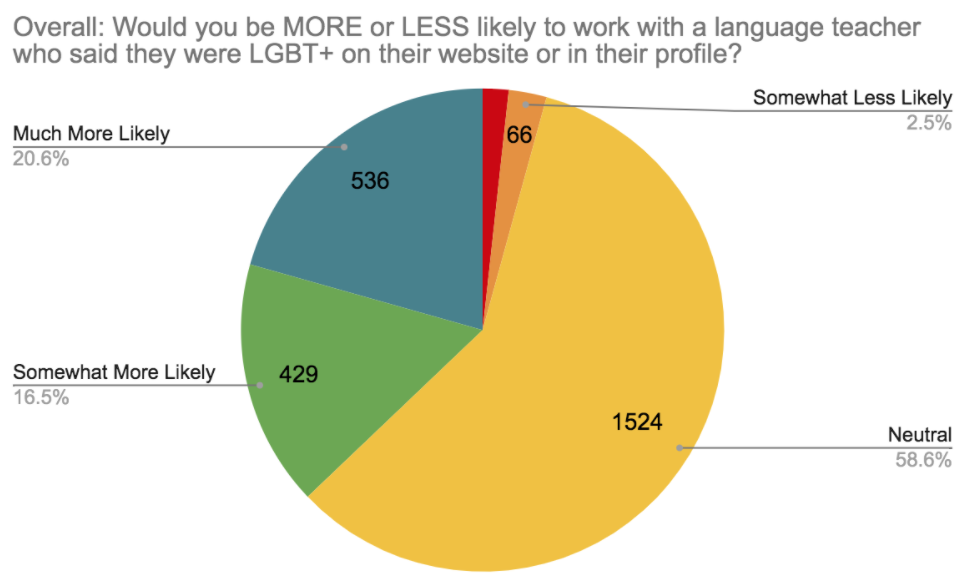

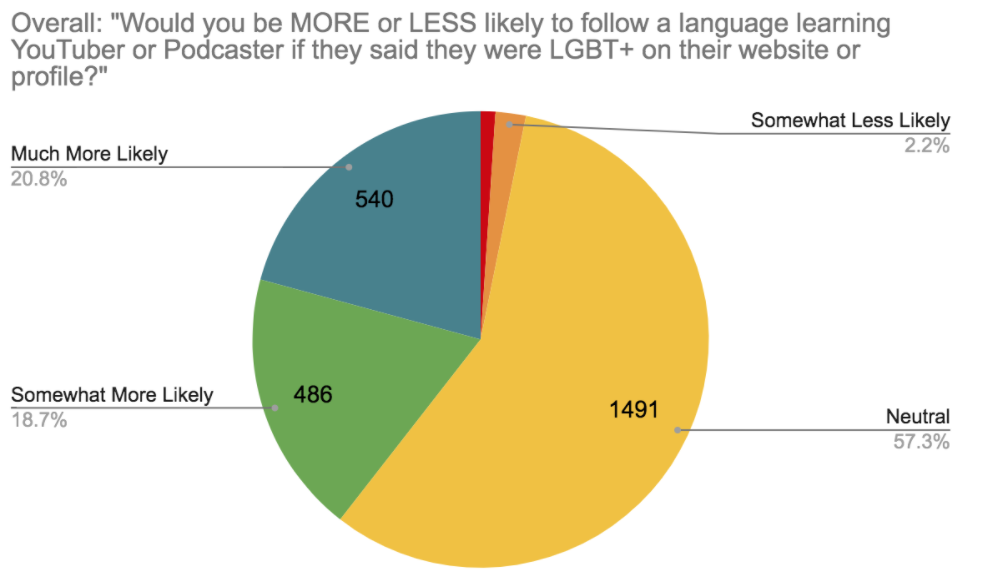

When asked if they were more or less likely to work with professionals who said they were LGBT+, language learners were overwhelmingly neutral, followed by more likely.

Only 4.2% were less likely to choose an LGBT+ teacher.

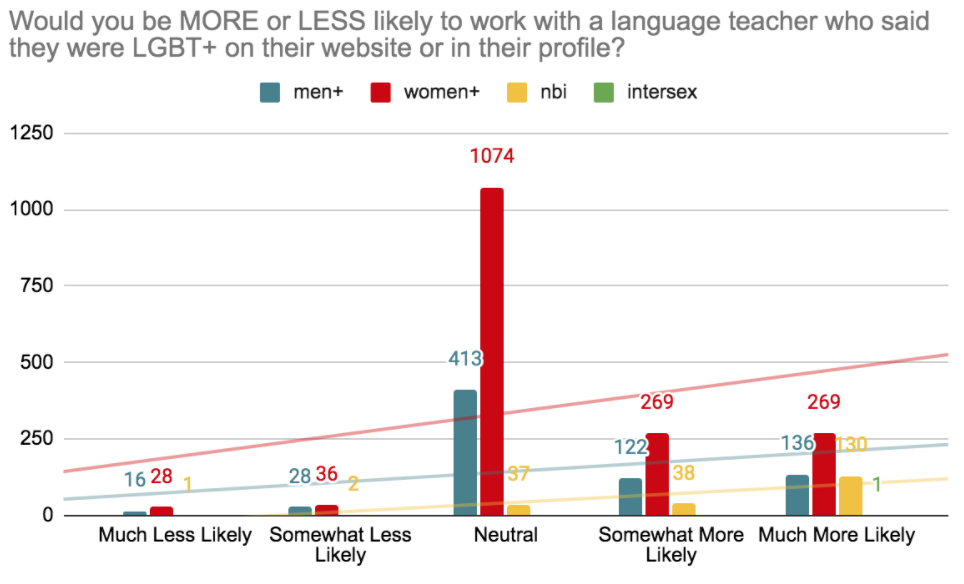

37.1% were more likely to choose an LGBT+ teacher. But considering that 51.2% of learners reported to be gay, lesbian, bisexual, or something other than straight (and some additional number reporting to be “straight” but not cisgendered), then it’s interesting to note that some percentage of LGBTQAI+ learners must feel neutrally on the question of a teachers’ own identity.

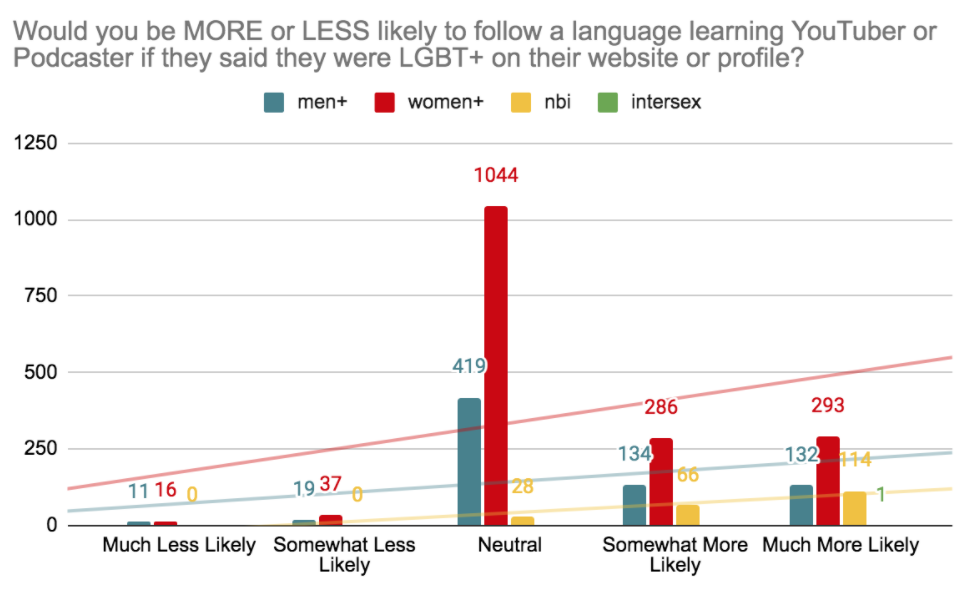

When broken up by gender however, the overwhelming majority of nonbinary learners were more likely or much more likely.

Women+ and men+ also trended more likely to work with LGBT+ identified teachers, but were significantly more neutral on the question.

When asked about whether or not LGBT+ identification would affect their choice of content consumption, the results were nearly identical for the group as a whole.

Only 3.2% of learners were less likely to follow an LGBT+ content creator (compared to 4.2% who were less likely to hire an LGBT+ teacher).

Once again, men+ and women+ remain neutral or positive, but nonbinary learners once again lean more likely to consume content by LGBT+ creators.

A key takeaway from this section, however, is that while 37.1% of online language learners saying they would chose an LGBT+ language teacher over a cishet teacher. Only 4.2% said they would be less likely to choose an LGBT+ language teacher over a cishet teacher (implying that they are more likely to choose a cishet language teacher over an LGBT+ teacher).

This should be contrasted with binary gender preferences. 56.7% of online language learners would said they would chose a female teacher over a male teacher. Only 5% said they chose a male teacher over a female teacher.

It’s unclear how these two data points interact (since LGBT+ teachers can be of any gender, and male teachers may be both LGBT+ or straight).

Key Findings on Other Influential Factors

In our final section of key findings, we wanted to look at other external and internal experiences that could predict (or lead to) a language learner’s ability to become a polyglot or hyperglot.

We decided to ask two questions about previous academic experiences:

- Do overall grades in school correlate with a learner’s ability to learn 5+ languages to fluency?

- Do language class grades in correlate with a learner’s ability to learn 5+ languages to fluency?

These questions were asked in the spirit of curiosity. Are language learners really just “smart”, or good students?

We also decided to test two additional hypotheses about the internal experience and learning process itself:

- Do certain motivations correlate with a higher number of overall languages learned?

- Does the absence or avoidance of stress correlate with a higher number of overall languages learned?

While questions about past academic abilities or experiences may predict the probability of a learner becoming a polyglot or hyperpolyglot, these questions were asked in the hopes that adult learners could use potential data to reflect within the learning process and use metacognition to adjust their study plan.

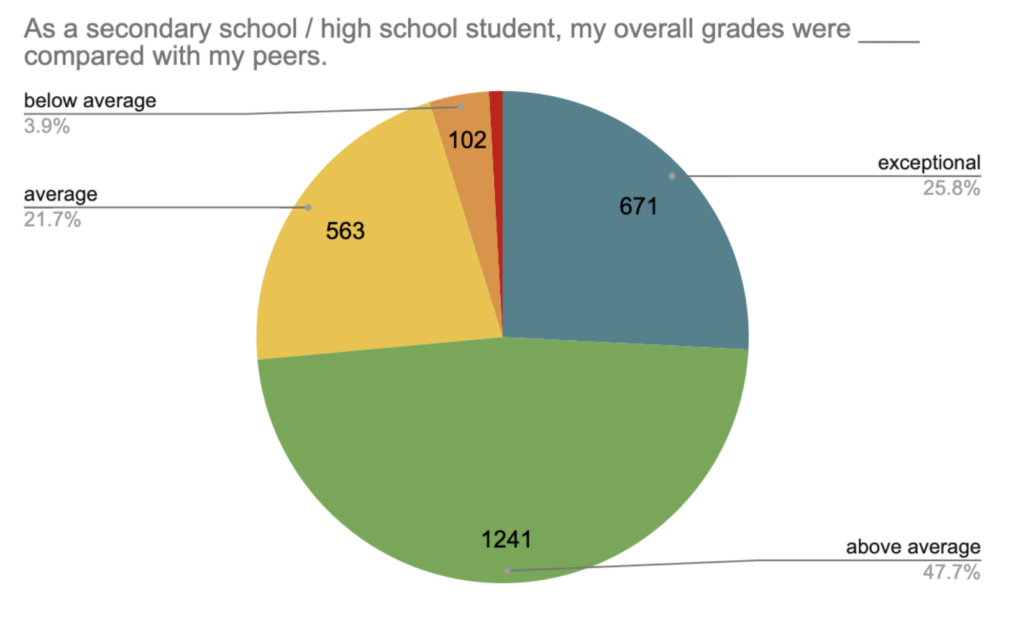

1. Do overall grades in school correlate with a learner’s ability to learn 5+ languages to fluency?

First, we took a bigger picture approach.

While the previous MIT studies have searched for some biological component to a language learning intelligence, we looked at how intelligence is often measured socially: through grades in school.

It should be noted that, once again, these results are self-reported. Additionally, they measure the survey participant against the “average” of their “peers”, which is open to layers of interpretation.

Nearly 75% of all online language learners reported to be “above average” or “exceptional”.

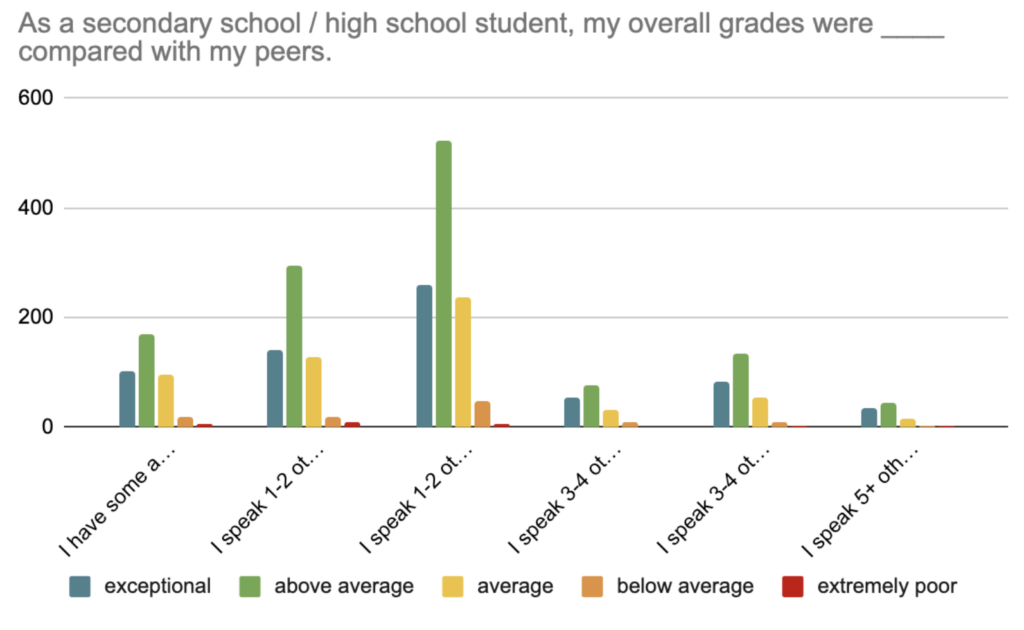

Interestingly, there seems to be no correlation between overall grades in school and number of languages spoken.

We might assume that in general, children who receive higher grades than their peers may attempt learning a language later in life, although those grades are no indication as to whether or not they will succeed.

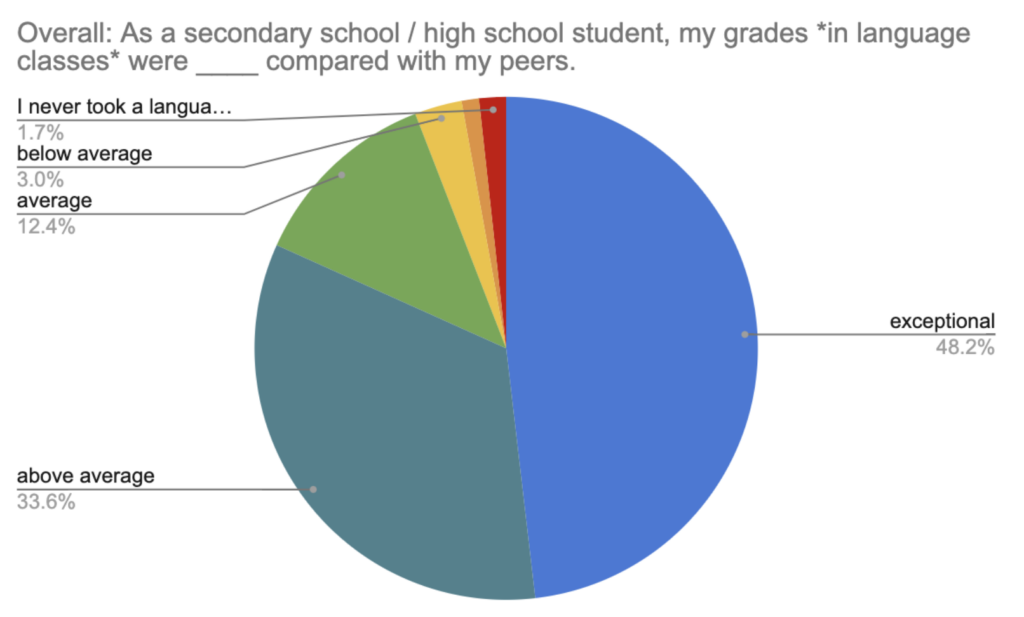

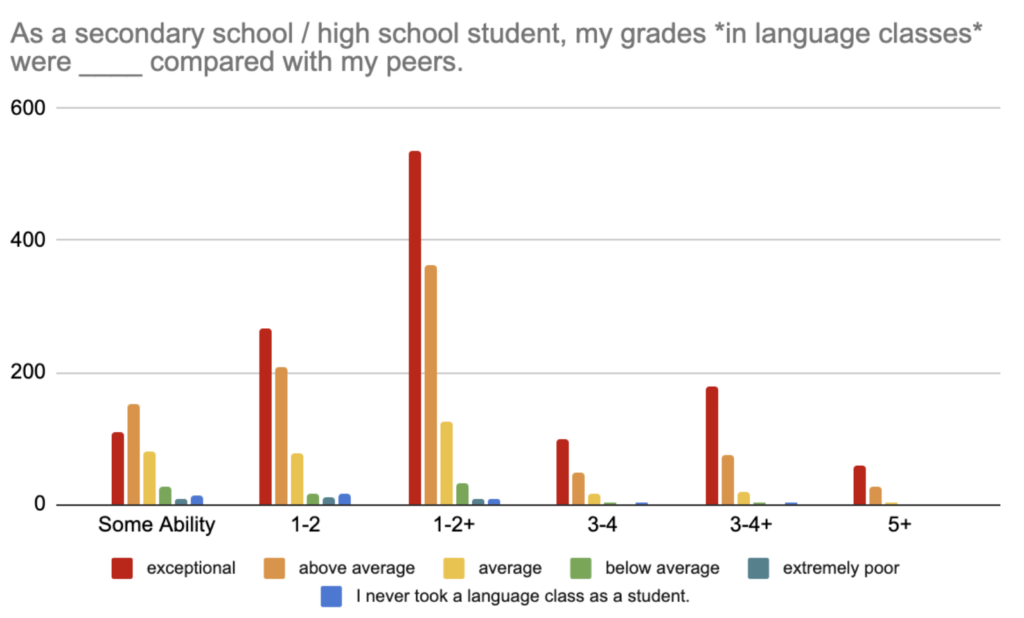

2. Do grades in language class correlate with a learner’s ability to learn 5+ languages to fluency?

When we look at grades specifically in language classes, we see over 80% of learners report to have gotten “above average” or “exceptional” grades.

We can see the data shows a slightly different story than overall grades.

While “above average” and “exceptional” language class grades may not be an indicator of how many languages someone can to out and learn in life, the learners with only some ability in additional languages were the only group to be more likely to report “above average” grades over “exceptional” grades.

We have to remember that both of these variables are self-reported, so it may be that learners who report “some ability” and “above average” are more conservative or modest in their reporting than those who reported to speak additional languages to “fluency” and claim to have received “exceptional”. Conversely, we there may be some correlation with the two variables.

The data shows that there may be some evidence to back up the stereotype that exceptional language learners must have been exceptional students. However, in the spirit of learners’ agency, it’s worth noting that at every single level there were learners who reported “below average” or “extremely poor” grades in both school and language classes.

Continuing with the goal of increased learner agency, we’ll now move on to two internal experiences a learner can gauge at the beginning part of their language learning journey: the reasons to learn a language and our relationship with stress.

3. Do certain motivations correlate with a higher number of overall languages learned?

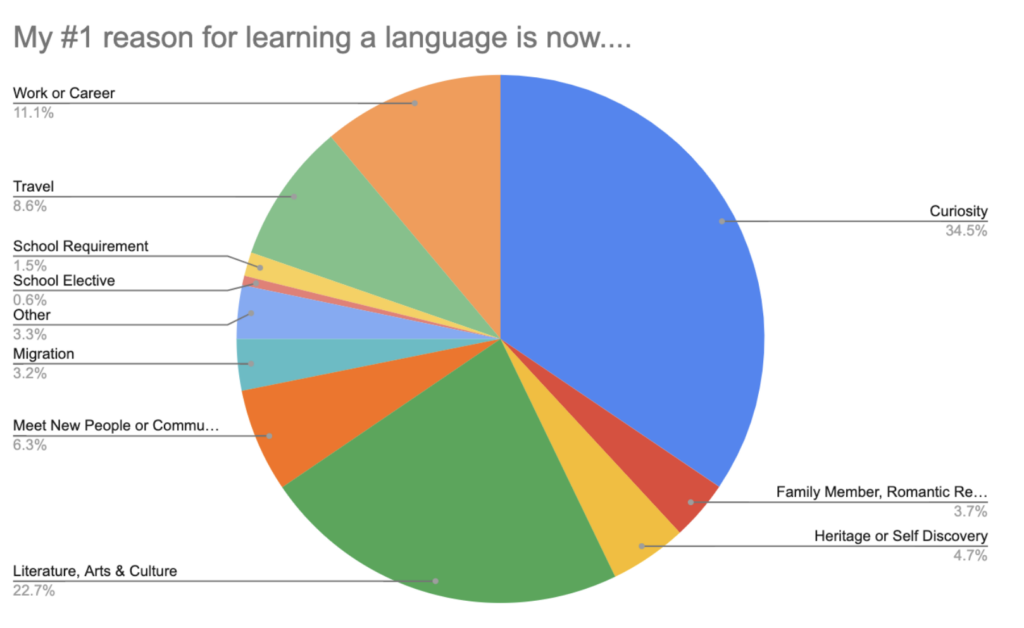

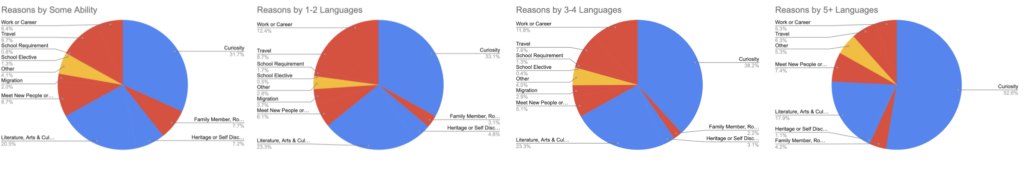

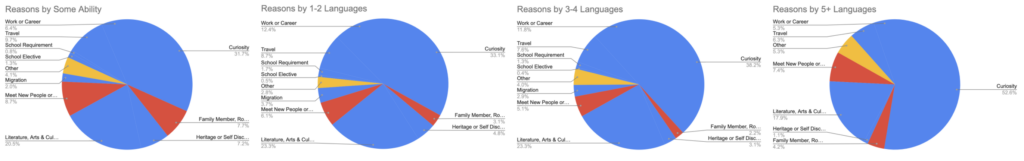

We then asked learners for their #1 motivation for learning a language.

When we look at motivations overall, we see a spectrum of answers and motivation within the community.

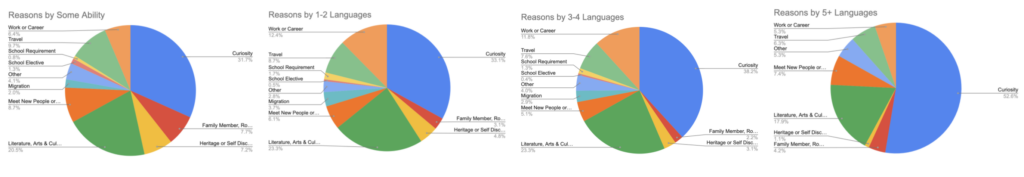

But do some motivations correlate with a higher number of languages learned?

When we separate the reported motivation by languages learned, there are several striking trends:

- The more languages a learner speaks, the more likely they are to cite “curiosity” as their main motivation.

- The more language a learner speaks, the less likely they are to list “family” or “heritage” as their main motivation.

- There are several motivations that remain largely consistent across any language learning level with no correlation to number of languages learned:

- Travel (ranging 6.3% – 9.7%)

- Meeting new people (ranging 5.1% – 7.4%)

- Literature, arts, and culture (ranging 17.9% – 23.3%)

We can also divide motivations into 2 umbrella categories: external and internal motivations.

- Internal motivations were defined as having primarily emotional, intellectual, or psychological components

- The only categories defined as internal were “curiosity”, “heritage or self discovery”, or “literature, arts, culture”

- External motivations were defined as having primarily social, legal, academic, or financial components

- Only “other” and “school elective” were excluded from this distinction because of a lack of data.

Interestingly, internal motivations were cited by all levels of language learners as slightly more important than external ones.

This was consistent across levels, although high achieving language learners were slightly more likely to cite internal motivation (71.6% of learners speaking 5+ languages, vs 59.4% of those with only some ability in other languages).

Finally, we can divide motivation into 2 additional umbrella categories:

- learning the language primarily to belong within a community

- Categories: “family member, romantic interest, or someone in my life” and “to meet new people or fit in”

- learning the language primarily to obtain a material or emotional benefit

- All other categories except “other”.

We can see here that obtaining a material or emotional benefit is by far the most popular reason to learn a language across number of languages spoken, with virtually no difference across language learning levels (83.1% of 5+ languages spoken vs 79.5% of those with only some ability).

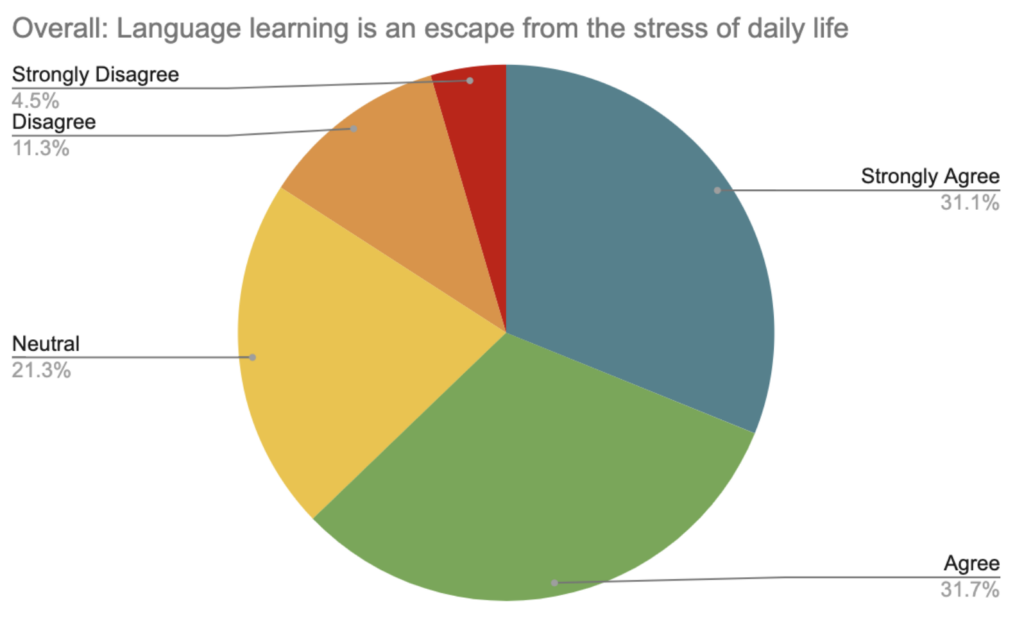

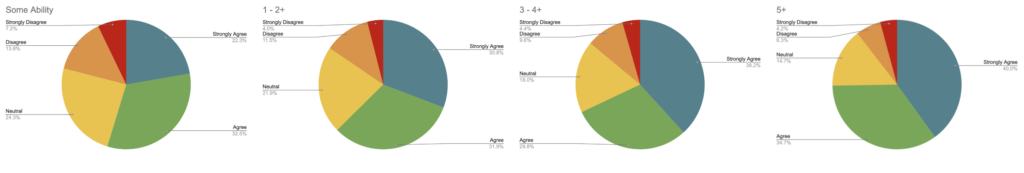

4. Does the absence or avoidance of stress correlate with a higher number of overall languages learned?

Finally, we return to stress as a factor for language learning success.

Overall, online language learners reported that “language learning is an escape from the stress of daily life.”

But does that belief correlate with number of languages learned?

When the findings are separated out by language, we see that the more languages a learner speaks, the more likely they are to agree or strongly disagree that “language learning is an escape from the stress of daily life”.

Along with citing “curiosity” as the main motivation for learning a language, the absence or avoidance of stress may be the single most powerful indicator as to the number of languages a learner can or will learn.

And when looking at internal experiences in the language learning process, we have a few key takeaways:

- Most language learners choose internal motivations over external ones, with high-achieving language learners being slightly more likely to be internally motivated.

- A learner’s curiosity directly correlates with a learner’s number of languages spoken.

- There is a direct correlation in feeling that “language learning is an escape from the stress of daily life” and the number of languages learned.

We also know from the previous sections on gender and community experiences that men+ are less likely to report being “nervous” or feeling “worry” than women and other gender minorities. Cisgender men are also the most likely to report speaking 5+ languages, although they are a minority within the community.

The links between stress, triggered by both external and internal circumstances, and language learning success should be studied going forward in future research.

Key Takeaways

Finally, we can look at the early academic experiences of a language learner and their contemporary internal experiences while learning a language.

Most notable is how many learners reported “above average” or “exceptional” grades in school. Earlier life experiences, both in school and out, should be explored in future surveys.

However, there is no solid correlation with grades given and number of languages learned in a lifetime.

Conversely, when we look at contemporary internal experience while language learning, we can see that there are some correlations between internal experiences and number of languages learned, although why those correlations exist is unclear.